While most minor wounds heal with just basic first aid, horses can have complications particularly with wounds on the lower parts of the limbs. It is not unusual for wound healing to be delayed by the development of large fleshy outgrowths known as proud flesh or more properly described as exuberant granulation tissue. Once proud flesh has developed a wound is unable to heal as effectively in the normal manner and frequently special treatments, including minor surgical procedures are required to remove the excess tissue.

Proud flesh: normal wound healing | why proud flesh forms | treatment | skin grafts | prevention

How a wound heals

As a wound heals, healing tissue provides a base upon which new skin surface cells are supported as they fill in across the wound to provide a healed surface (surface epidermal migration). Normal healing tissue looks red-pink in colour and has a flat surface. Treating horse wounds correctly helps promote healing.

While the surface skin cells are moving across the wound, they produce chemical signals that encourage the cells in the wound margins to contract. This pulls the sides of the wound towards each other. This “wound contraction” reduces the distance the cells have to move, hastens the closure of the wound and assists in expressing any dead or foreign matter.

The combination of healthy granulation tissue, epidermal migration and contraction form the main basis of wound healing. Once skin cells cover a wound, the normal granulation tissue production is switched off and the process of deeper remodelling and repair can proceed.

Why proud flesh forms

If the healing process is impaired, the delicate balance between the various processes can be upset. If contraction and the migration of skin surface cells are inhibited then the wound may get bigger because granulation tissue is the only active process happening. This results in bulging masses of tissue, which usually looks rather knobbly, pink and shiny. It may also have a yellowing tinge and may bleed easily if knocked. Sometimes the tissue can protrude out of the wound and look like a pink cauliflower.

There are many reasons why a wound doesn’t heal as expected, which include infection, foreign bodies, dead tissues or movement within the wound site, chemical applications and poor blood supply to the wound. All these factors can encourage exuberant granulation tissue and inhibit the spread of skin cells across the surface of the wound. Infection and excessive movement are the most likely reasons why horse wounds develop proud flesh.

Where proud flesh develops at sites other than the lower leg regions, there is usually another definable cause, such as a foreign body embedded deep in the wound.

Proud flesh: treatment and aftercare

Appropriate veterinary advice is required to decide on the best treatment options. Sometimes thorough wound cleaning and topical creams may resolve minor amounts of proud flesh, along with firm bandaging to reduce movement and help wound healing. Sometimes laser therapy can help and occasional caustic substances can be recommended.

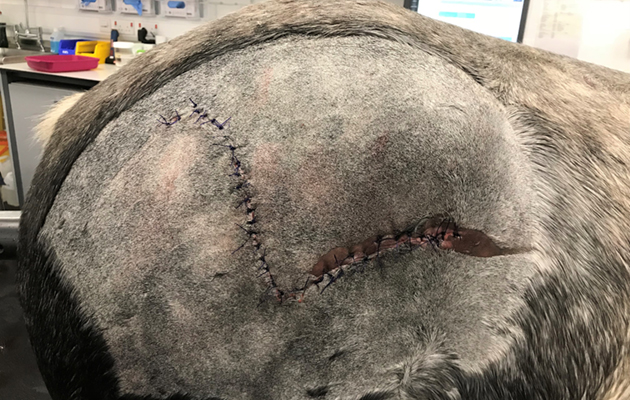

A wound with an excess of granulation tissue is often most effectively managed surgically. Usually, this involves cutting back any excessive tissue. While this is invariably a very bloody business, it is usually painless because granulation tissue has minimal nerves or nerve endings.

While the removal of small amounts of proud flesh can be done in a standing sedated horse without any need for local anaesthetic, it can be applied to numb the surrounding area when necessary.

General anaesthesia is very rarely required, except possibly in cases dealing with very extensive proud flesh, where it may useful to help aid the aggressive control of the heavy bleeding that will occur.

Surgical debridement (cutting back) can serve several purposes. It reduces the bulk of the wound and, at the same time, will remove many of the “blocks” to healing. It is common practice to cut the proud flesh back to just under the skin level. This may allow the skin edges to contract and cells to migrate across the margin of the wound.

However, where proud flesh has been present for some time, the margin of the wound could be unhealthy and the sensitive edges of the wound may have to be cut back. Treatment is focused on creating a healthy wound that wants to heal.

Careful wound dressing management immediately after such surgery is vital — dressings are usually changed every 24hrs. At this stage, the vet will reassess the wound and make a decision as to the likelihood that it will heal naturally. Sometimes, immobilisation of the wound site under a firm bandage or cast is needed.

Infection may need to be controlled with antibiotics after appropriate culture and sensitivity to identify the causative bacteria and reduce the risk of antimicrobial resistance.

Skin grafting

If the wound shows evidence of healing over the next four to seven days, treatment is continued. Sometimes the process of healing can be hastened by the simple expedient of skin grafting.

The easiest form of this elegant yet simple procedure is the use of small skin pieces removed from a healthy site (often the side of the neck under the mane), which are deposited into the granulation bed.

This “imports” normal skin with a strong tendency to heal into the wound, and within a few weeks the tiny islands of new skin will be visible in the bed of granulation tissue. The grafts encourage the wound to contract and reduce the flow of new blood vessels, thus encouraging the spread of skin cells across the surface of the wound.

If skin grafting fails, the possibility of other wound healing complications must be considered.

Prevention of proud flesh

Prevention of proud flesh is easier said than done, but a healthy, uninfected, clean wound that is properly managed from the outset is less likely to develop it. As healing relies upon the migration of the delicate skin cells, repeated application of chemicals and even repeated washing and rubbing of a wound can interfere with the healing process and encourage proud flesh.

Once a wound has been cleaned, a sterile hydrogel is recommended as the best way to keep the wound moist while absorbing bacteria, damaged tissue and debris under a suitable dressing. It can be gently cleaned away and replaced when the dressing is changed.

Vetalintex, £7.32 at amazon.co.uk

This cleansing and sterile hydrogel encourages a moist wound condition to help aid recovery.

To dress a wound, apply a sterile pad then an absorbent layer, such as cotton wool, and a clean bandage. The size, firmness and thickness of the dressing is determined by the amount of discharge from the wound and the necessity to immobilise the skin edges or adjacent structures such as joints. Daily dressings changes are normal in the early stages, reducing to every three to five days or as your vet advises.

Melolin, £6.39 at amazon.co.uk

This pack of 20 10x10cm non-stick dressings are individually wrapped and can be used for all sorts of minor injuries.

Depending on the position of the injury, limiting the horse’s movement during the early stages of healing may help avoid the application of additional stress on the edges of a wound as it closes together.

The key thing to realise is that no two wounds are the same, and they change from day to day. If you are concerned by any delay in healing or any unexpected changes in a wound, contact your vet.

You may also be interested in…

Alternative ways of treating wounds *H&H VIP*

When a wound won’t heal, antibiotics may not be the answer. Professor Debra Archer discusses unusual treatment options, from maggots

Wound closure and effective stitching techniques for horses *H&H VIP*

Good wound closure is critical to effective healing. Patrick Pollock FRCVS looks at modern methods — and explains what to

Equine first-aid kit essentials: what you really need

If you're unsure about what you should have in your horse’s first-aid kit, then we are here to help...

Puncture wounds – a potentially serious injury that can be easily missed

Sarcoids in horses: what every horse owner needs to know

Tetanus in horses: what every owner needs to know