The £150 “jumping machine” became a household name and propelled Pat Smythe into superstar status, discovers Pippa Cuckson

WORDS like “superstar” and “celebrity” are readily bandied around nowadays. Pat Smythe truly earned those accolades, in post-war days when it was unusual for girls to trounce men at their own game.

Pat’s fame was buoyed by unprecedented newspaper fascination in showjumping, and from Pathé newsreels shown in cinemas. She met Generalissimo Franco, the Pope, Hollywood star Danny Kaye and dined with the ex-King of England, the Duke of Windsor.

Pat won more grands prix than anyone else of her generation, even though women were excluded from many in the early 1950s.

Not surprisingly, Pat’s horses became household names, too, not least the 15hh grey Tosca, whose popularity continued long after she retired to stud. Tosca’s first foal Lucia was celebrated in Illustrated magazine – the 1950s equivalent of a photoshoot in Hello!

Impetuous but ultra-careful, Tosca was often in the shadow of her stablemate Prince Hal, with Pat herself occasionally surprised when Hal was selected over Tosca for Nations Cups. Over two years, Tosca averaged one big win a week. In 1953, she cleared 100 consecutive fences in championship classes over the Windsor-Richmond-Brighton fortnight, rivals christening her the “jumping machine”.

at home in Gloucestershire with Tosca and Hal in 1953 – the pair became skilled at two-horse grands prix, where Pat would jump from one horse on to the other

TOSCA joined Pat’s Cotswolds yard in late 1950, along with Hal and another solid performer, Leona. It was none too soon – the 20-year-old Pat had been devastated by the sale of first horse Finality at the end of 1948, and thought her career was already over. She bought Tosca for £150 from Alan Oliver’s father Phil, untried in the ring because she was so wild. Like most Irish horses, Tosca’s background was unknown; likely part-Connemara and bred in the “bogs” where, said Pat, “a friendly dealer will provide the name of any sire of your choice”.

Pat’s first discovery was Tosca’s terror of rattling buckets; she pinned Pat in the corner when she first went in with feed. And the Olivers were right – Tosca was uncontrollable. The first time Pat rode her at home she ran away, after falling through a stone wall. In desperation, Pat pointed her at another big wall and drop.

“Luckily she was wise and stopped before this dangerous leap,” wrote Pat.

Pat holds a statuette of “star performer” Tosca in 1954

Pat had done little flatwork with her other horses, so realising Tosca would take months of rehabilitation, she passed the groundwork to future husband Sam Koechlin, an eventer visiting from his native Switzerland for the “new” competition at Badminton.

Jumping training then commenced over rustic poles and oil drums in Pat’s rented paddock, whose homespun appearance was often a surprise for visiting media. When the ground became hard, Pat spread sand around the fences. In an effort to avoid this alien footing, Tosca started landing hindlegs first. Things got worse before they got better; it was six months before they attempted novice shows.

Incredibly, Tosca qualified for the 1951 Horse of the Year Show (HOYS). Pat was determined she would become the model of good schooling and was teased by team-mates for entering the prix caprilli – dressage and jumping – which they won.

The Harringay debut showed more than a glimpse of Tosca’s future brilliance. She also won the touch-and-out Lonsdale Stakes, clearing 22 fences to the runner-up’s 13, and jointly won the British Showjumping Association (BSJA) spurs for best horse. For the next three years, she would win them outright.

Pat had lost her father in her teens. On an icy January morning in 1952, her mother was killed in a car crash. With death duties to pay, a horse had to be sold. Pat would never part with Tosca or Hal, so bade Leona farewell.

With Hal on loan to the Olympic squad in spring 1952, the grieving Pat invested herself in Tosca. At Oxford County, she won four classes in two days without lowering a fence. From there Tosca went to one of the era’s premier shows, Richmond Royal, winning the puissance and coronation champion cup. At Brighton, Tosca took the South of England championship, and at The Royal, the Walwyn FEI championship.

More wins racked up, and at her first Royal International, Pat and Tosca were picked for the 1952 Prince of Wales cup team, the first time women riders were allowed in a Nations Cup. Britain won on four faults – second-placed USA had 29. Tosca also finished second in the Queen Elizabeth II and Daily Mail cups.

Pat aboard Tosca at home in 1952, leading Prince Hal and Candy

At HOYS 1952, she again won the Lonsdale and the BSJA spurs outright, then set off for her continental debut in Brussels, where Tosca and Hal claimed the two-horse grand prix. Tosca was leading money-winner of 1952 by a margin of £500.

UNDER amateur rules at the time, Pat could not accept riding fees, train other people or horses, and commercial sponsorship was unknown.

She could not cover her bills from the small prize-money available in the 1950s. Until 1953, she could only afford to insure Tosca for £200 (about £6,000 in today’s money.)

So Tosca’s record is light on overseas wins simply because riders had to self-fund all foreign trips and Pat, despite her profile, could not afford it. She wrote that “for every visit abroad I may miss 20 successful competitions at home with far less strain on the horses”. Pat boosted her income by writing, turning out 11 bestsellers in four years.

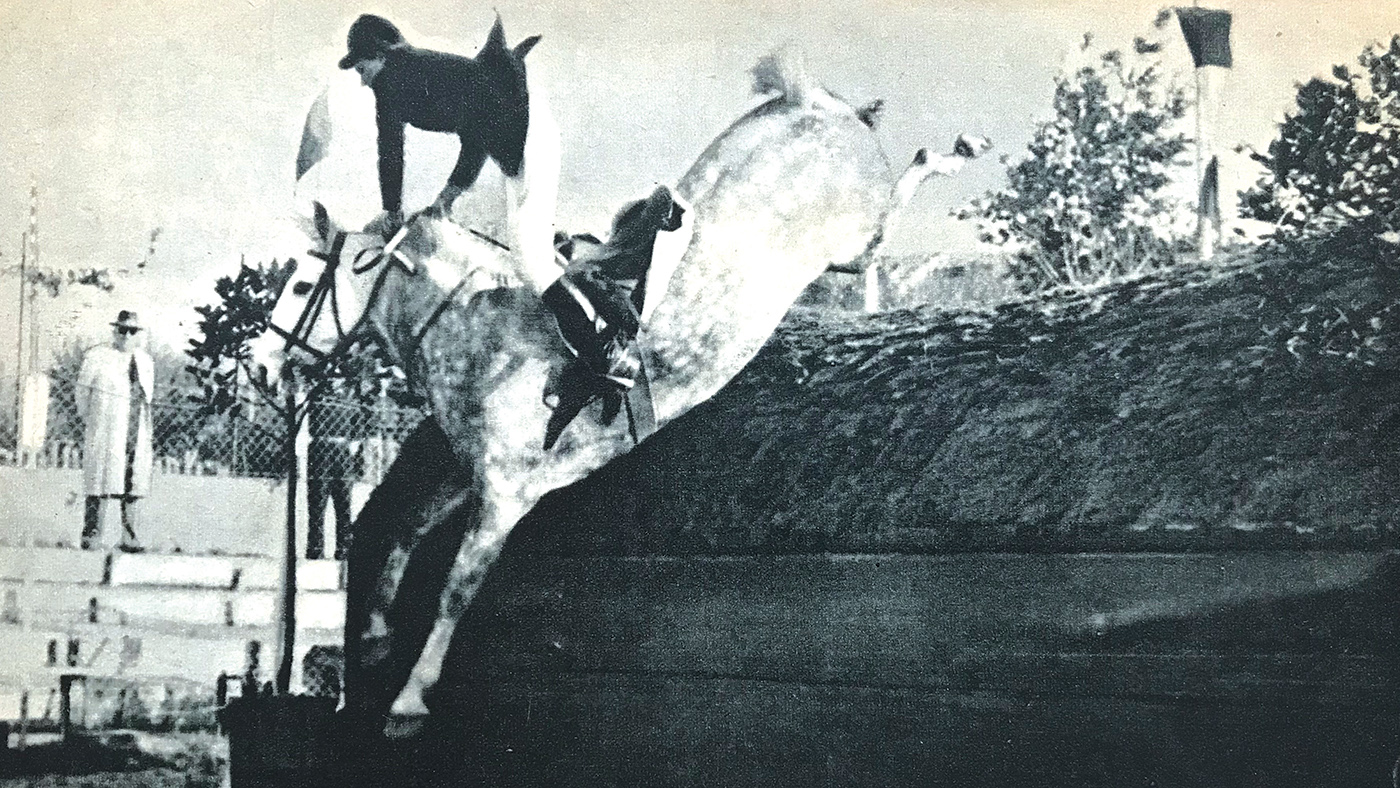

All began well in 1953 in Marseilles, the start of a spring French Riviera/Italian tour. But in Nice, Tosca had a serious accident at a “trick” bank – 8ft high, constructed from wet sods and baked hard by the sun. Many horses fell, including Tosca who attempted it in one leap. Pat remounted and only realised she herself was hurt when noticing her blood-soaked breeches – a gashed thigh from Tosca’s studs was heavily stitched. Pat hobbled on to Rome, where she was presented to Pope Pius XII, but unable to kneel as protocol required. Worse still, Tosca was badly shaken so was sent home for confidence restoration at local shows.

In the autumn of 1953, Pat and Tosca made the journey to the USA to take part in the North American tour

Tosca was back on form by Richmond, going through at the card at so many Royal International prep events that Pat need not have returned the trophies won in 1952. Tosca was again picked for the Royal International’s Nations Cup, where Britain led so handsomely that Harry Llewellyn and Foxhunter didn’t jump the second round.

Left: in 1953, Tosca cleared 100 consecutive fences in championship classes over a fortnight, including taking the ladies’ national title at Brighton

That autumn, Pat achieved her ambition to contest the North American tour, so was dismayed by the “atrocious” amenities at Madison Square Garden in New York, with nowhere to exercise.

Grands prix combining two horses’ results were by now a speciality for the Tosca and Hal double act. They found their form in time to win the two-horse President of Mexico trophy.

“They always clung together like young sweethearts to help my ‘flying change’”, Pat recalled, referring to the necessity of jumping from one horse to the other.

in action in the Queen Elizabeth II cup at White City

On her Irish debut in 1954, Tosca won Cork’s An Tóstal championship, despite the low-set floodlights “blinding” many horses.

Left behind during Pat’s next European tour, Tosca became fat, but despite lack of work she claimed her third Selby Cup in the Royal International, and was second again in the Queen Elizabeth. She won the North of England title at the Blackpool international despite coming down with a mysterious “poisoning” of the glands. This illness became life-threatening, though she recovered, and won the BSJA spurs again at HOYS in 1954 and the Sunday Graphic cup.

GIVEN the intensity of her competition schedule, Tosca was amazingly sound in limb – but not in wind. Over the winter Pat became increasingly worried about Tosca’s cough and, on veterinary advice, retired her in early spring 1955. Tosca was barely 11.

Tosca and Pat suffered a serious fall over an 8ft bank in Nice, France

Pat decided to purpose-breed showjumpers from Tosca, the subject of another learnt book and an ambitious project for its time. Pat largely chose thoroughbred stallions from the affordable Hunters Improvement Scheme.

First foal Lucia was never broken in, having injured her stifle jumping a bank in the paddock as a precocious foal. Seven of Tosca’s other progeny went on to compete.

“Tosca was never kept so busy as when Lucia arrived. There must have been times when she regretted passing on so much character to her daughter,” recalled Pat.

Once retired, Tosca went on to breed a number of foals, seven of whom went on to compete

Pat’s books record her despair over the old Irish ways of backing a horse and riding it to hounds the same week, the likely cause of Tosca’s early unruliness.

“Tosca’s character and temper could easily have become difficult in the wrong hands. However, this trait is a proof of courage, without which one cannot find a star performer,” she said.

Badminton glory

TOSCA won at Badminton – in the literal sense. In its early years, showjumping classes ran alongside the horse trials to help attract crowds. Tosca – having first refused to load – arrived just in time to win the 1954 Badminton grand stakes. She received her prize from Princess Margaret, who watched from a wagon in the middle of the ring, and at whose feet Pat had been deposited by Hal.

Reflecting on the new British interest in eventing, Pat praised the dedication and patience of the riders and noted that spectators were “bringing their cars and families from far counties.”

“We had an awareness that Mother was famous”

THE Koechlins lived in Switzerland from 1960 until Sam’s death in 1985. Pat then lived in the Cotswolds until her death in 1996, aged 67.

Monica Koechlin says that she and sister Lucy regret paying so little attention to their mother’s reminiscences.

“I remember being sat on a woolly [1956 Olympic bronze medallist] Flanagan when I was three,” said Monica. “ I also remember hearing about Tosca. Mother always said she was so very brave over those huge jumps, the horse who propelled her to real stardom.

“Growing up, we saw a very different sort of rider. Mother had a lot of injuries over the years and had both hips replaced, so she just hacked out with us on our ponies.

“We had an awareness that Mother was famous, but your parents are your parents and you brush it aside – every child wants to create their own experiences.

“I remember a school trip to the Aeolian Islands, where other English visitors discovered who I was and wanted my autograph! We’d hear how fan letters from Australia found Mother when simply addressed ‘P Smythe, England’ – it was all rather surreal.

“I’d so love to have been there to see it all, though it’s now fascinating to watch the old footage online. One thing I do know is that she’d be delighted to think people are interested in her horses, all these years later.”

You can also read this feature in the 13 May issue of Horse & Hound magazine.

You might also be interested in…

Positive news as major events prepare to welcome fans *H&H Plus*

‘This is a nice boost’: Spectacular double for Ben Maher *H&H Plus*

Laura Kraut on her Olympic hopes, injuries and supporting her partner Nick Skelton in Rio *H&H Plus*

Mister Softee: David Broome’s ‘freak’ with ‘bucketfuls of heart’ *H&H Plus*