Giant leaps forward in surgery have revolutionised wound closure. From the bone needles and strips of intestines or gut used throughout the ages, treatment is now enhanced by innovative equipment. Wounds are stitched with needles made of metal, plastic and other synthetic materials, closed with staples, surgical tape or glue, or “welded” using laser technology.

Good wound closure not only speeds up the healing process, but can also reduce scarring, prevent tissue spaces under the wound filling with fluid and reduce the risk of infection.

Whether created by the surgeon’s scalpel or a strand of rusty fence wire, a wound will elicit a biological process in all mammals. This series of natural steps begins with a burst of inflammation which is critical to getting the healing process under way. Recent research has shown that this is where problems can start with equine wounds: this inflammatory phase appears less effective in the horse than in dogs, cats, humans and other species.

The wound then rids itself of dead tissue and contamination — a process called debridement — and begins to repair. Granulation tissue (proud flesh) will appear about four days after wounding, followed by a white rim around the edge of the site at around 10 to 14 days. This rim is the advancing epithelium, a layer of new skin cells that migrates across the surface of the wound and causes it to contract and reduce in size.

Healing time

Perhaps the greatest discovery about wound healing emerged in the late 1960s, when research revealed that wounds healed roughly twice as fast if they were covered to prevent scab formation and kept moist. We still use this theory today. If a wound cannot be closed, new cells move over the surface at a rate of 1.2mm per day — which means that a typical equine limb wound of around 20cm in diameter will take nearly three months to heal.

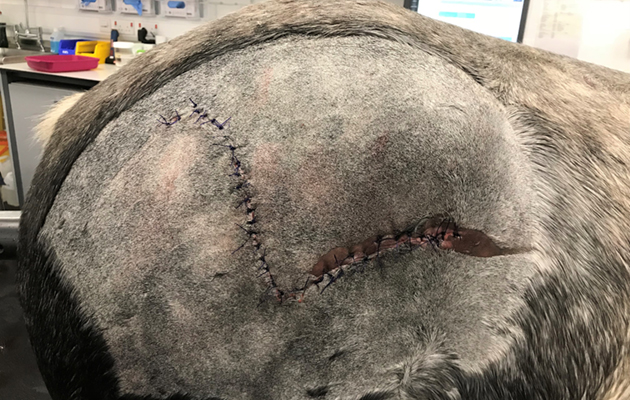

Therefore, vets are keen to suture (stitch) a wound as soon as it occurs. If its edges can be kept together (primary intention healing), healing time is quicker and the cosmetic result better.

Where possible, a vet will draw the edges of a wound together, rather than leave it open to close by itself. To be effective, the wound margin must have a good blood supply and the tissue must be free from contamination and infection. The wound edges will have to be immobilised, so they must not be under excessive tension.

Increasingly, vets employ a technique of delayed closure for wounds that do not meet these criteria. New innovations such as hydrosurgery (literally cutting with water) or aggressive debridement are used to prepare the wound for closure between two and four days later.

If tissue is present and it remains vital (living), eventual closure should be achievable. Even wounds with ragged edges or missing tissue can be closed — or partially closed — but this may not be possible for those with necrotic (dead) tissue, a large deficit (hole) or heavy contamination.

Only when there is something definitely wrong will a wound not heal. Primary inhibitors of healing include the presence of infection, necrotic tissue or foreign bodies within the wound, or poor oxygenation or reduced blood supply. Movement, continued trauma or tissue deficits will also prevent healing, as will local factors affecting the injured site or additional health problems.

Sew strong

Deeper wounds are closed in multiple layers, using principles developed in human surgery. This restores the continuity of the tissue and eliminates spaces that may fill with fluid and increase the risk of infection, as well as preserving blood supply to the wound and minimising tension.

Sutures made of non-absorbable materials are mainly used within the skin, or where the material must maintain its strength for the life of the animal. Absorbable sutures are broken down by several natural processes, but are designed to be as “inert” as possible so as not to cause an inflammatory reaction. They lose their strength at a defined rate, allowing the surgeon to select a material that lasts until the tissue being repaired has enough strength of its own.

Nevertheless, all sutures represent foreign material to the horse and result in some reaction, so strict surgical techniques must be adhered to during wound closure, to reduce infection risk. Bacteria are known to attach to the surface of suture material and are much more difficult to eliminate with antimicrobials once established in colonies. In the worst cases, the suture must be removed to eliminate infection.

Metal staples are quick and simple for wound closure and very much geared to field and emergency scenarios. Following recent concern that risk of infection is high, however, many vets have moved away from using them in hospital situations.

Cyanoacrylate, or wound glue, is also used to “stick” wound edges back together — a useful treatment for small, superficial wounds or for those in more unusual places such as the cornea (the surface of the eye).

Wraparound care

The initial treatment of a wound can make a big difference to outcome. As soon as you notice the injury, wash the site carefully to reduce contamination using a saline solution (add one teaspoon of household cooking salt to 500ml of boiled then cooled water) or water from a hose.

In humans, every hour saved before a wound receives lavage (flushing with water) means that the risk of wound infection is halved.

If bleeding is excessive, cover the wound with a clean dressing and a bandage until the vet arrives. Do not apply any cream, ointment or spray until the wound has been assessed.

Seek veterinary advice as soon as the wound is sustained, rather than waiting until complications occur. The temptation is to trivialise small wounds, yet these can be problematic. Sending a photo to your vet can help if you’re unsure whether or not a wound needs expert attention.

The process of healing may continue for some time after the wound has apparently repaired itself. During this “maturation phase”, the new tissue undergoes extensive remodelling. This new skin is fragile; indeed, a healed wound never fully regains the strength of the original skin.

All scars are potentially fragile and should be protected for a prolonged period, perhaps forever, using a support bandage or a boot. Some scars, particularly those caused by a very large wound with extensive tissue loss, lack normal skin components such as sweat and oil glands or hair follicles. The area may become dry or scaly, requiring protection during exercise or moisturising treatment for the rest of the horse’s life.

Ref Horse & Hound; 6 December 2018