Equine vaccination rates in the UK remain dangerously low. It is estimated that fewer than half (approximately 48%) of the 250,000 or so horses based here are adequately protected against the highly contagious equine influenza virus or the frequently fatal tetanus.

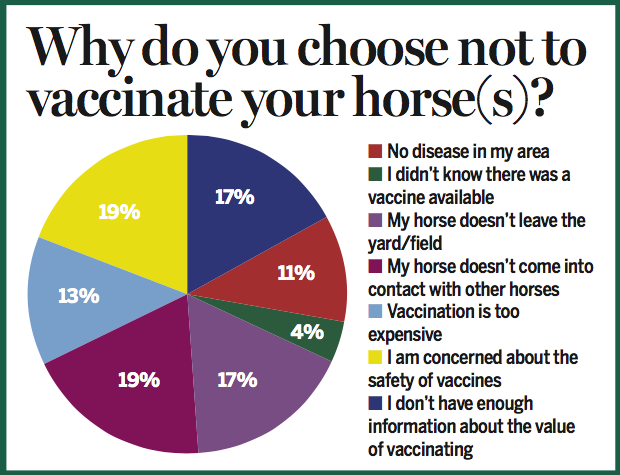

Following the recent equine flu outbreak in the racing world, the topic of vaccination has come to the forefront of many horse owners’ minds. Immunisation for both flu and tetanus can cost as little as £50, so why are so many choosing to skip this safe and affordable prevention measure? According to a recent online survey (see box, below), most of the reasons for non-compliance with a national vaccination programme appear to be due to a lack of understanding about disease risk and misconceptions surrounding the vaccines themselves.

Nearly 40% of the 1,649 owners who responded said they chose not to vaccinate because their horses never leave home or come into contact with other horses. But unless you live on a remote island, your horse is in direct contact with other horses — through the movement of people and pets from neighbouring farms, fields and yards.

Equine flu can spread rapidly between unvaccinated individuals, while the virus has the potential to travel up to five kilometres under favourable weather conditions. Even those horses on isolated premises remain at risk.

Tetanus is caused by the spore-forming bacteria Clostridium tetani, which can survive for long periods of time within soil. Unvaccinated horses, ponies and donkeys of all ages and types are therefore vulnerable, even if they never leave the field.

Where there’s mud, there’s the chance of tetanus as bacteria can survive for long periods of time in soil

One in five owners expressed concern about the safety of vaccines. In my opinion, this stems from historic, unsubstantiated reports within the field of human vaccines and also from the occasional cases where a horse experiences a reaction. In reality, rates of severe reaction are low: of the several thousand vaccinations given every year at our practice, I can count the affected horses on one hand — with digits to spare.

While it is relatively common to see localised muscular swelling or soreness after vaccination, or transient, self-limiting signs that include fever, anorexia and lethargy, reaction rarely becomes life-threatening.

Some owners believe there is no disease in their area, so choose not to vaccinate. It is true that we rarely hear of outbreaks unless there are widespread health implications, yet few people realise that there is always a low incidence of certain infectious diseases within the UK.

These cases are usually sporadic and are controlled with local veterinary intervention and national monitoring. Even though clinical disease can become an issue, the isolated nature of these outbreaks does create a worrying complacency over the need for routine vaccination.

Diluting the risk

Vaccination protocols set out by vets and governing bodies aim to minimise the risk to individual horses and also the equine population at large.

All horses should be vaccinated in accordance with the vaccine manufacturer’s guidelines. These guidelines do change, however. This is often because governing bodies such as the World Organisation for Animal Health, and monitoring entities such as the Animal Health Trust, modify recommendations in accordance with data collected — not only within the UK, but globally.

It is important to understand that no vaccine is 100% effective. There are different types of vaccine and methods of administration, yet they are all designed to prime the horse’s system to provide some degree of immunity. If a vaccinated horse comes into contact with the pathogen (the bacteria or virus), clinical symptoms will be lessened and the horse is likely to recover with minimal intervention.

Another key point with contagious diseases such as equine flu is the concept of herd immunity. Vaccination of the majority of horses “dilutes” the risk of exposure of unvaccinated individuals to the causal agent of disease — which works in local yard set-ups and at a national level involving the whole UK herd. But herd immunity is only possible when at least 70% of the population is vaccinated, otherwise the incidence of clinical disease becomes more prevalent.

Some owners might argue that a case of equine flu is no big deal. Bear in mind that a previously fit, healthy horse affected by the virus may not be back in full work for six weeks. An older horse with concurrent health issues may take longer to recover and is at additional risk of complications. Consider, too, the practical issues and economic impact: one case at a large yard may mean no hacking or competing for anyone else.

With tetanus, herd immunity does not apply. Neither is it true with equines that “five for life” will leave you covered, as is thought to be the case with human tetanus vaccination. Going out in a field and just being a horse means that the level of exposure to tetanus infection is higher. The smallest scratch or puncture wound is sufficient to allow bacterial entry, so vaccination over the course of a horse’s lifetime is vital to establish protection.

A deadly disease

It is unusual as an equine vet to encounter more than a handful of tetanus cases throughout a career. Our practice has recently seen two cases in unvaccinated horses within a month of one another. One survived, with considerable medical intervention (see case study, below), but the other horse died — highlighting the potentially fatal nature of the disease.

There are currently several different diseases we can vaccinate our horses against, so your vet can suggest an appropriate immunisation programme based on an individual’s age, health and exposure risk. My advice would be to vaccinate all horses for equine flu and tetanus, at least. As these particular owners can now testify, vaccination has the potential to save huge amounts of time, money and heartache.

Case study: surviving against the odds — how Star survived tetanus

The toxins produced by the tetanus bacteria can have a devastating effect on a horse’s nervous system.

When nine-year-old mare Star appeared to choke on a piece of carrot, her owners called us at Farr and Pursey Equine Veterinary Services. Difficulty in swallowing and opening the mouth is, in fact, a typical sign of tetanus and the reason why the disease is sometimes referred to as “lockjaw”. Star also had the classic “rocking horse” stance and raised tail, and was transferred immediately to the Royal Veterinary College (RVC).

“The aim of treatment is to bind any loose tetanus toxins, so Star was given high doses of the tetanus anti-toxin,” says Dr Bettina Dunkel of the RVC. “She also received intra-muscular penicillin, in case there was still any active infection, and intravenous fluid therapy with supplementary glucose because she was finding it difficult to eat and drink. As tetanus affects the nerves, we put cotton wool in her ears to decrease any stimulation from noise.

“We think that Star may have been vaccinated in the past, which provided some underlying immunity, but she was extremely lucky to pull through,” adds Bettina. “The survival rate for tetanus is around 30%. Prognosis is very poor if the horse has already gone down, while further complications can include aspiration pneumonia caused by breathing problems.

“After a week of treatment, Star was stable enough to return home to recover further. Long-term prognosis is good once the toxins have left the system.”

About the author: Ricky Farr, B.Sc (Hons), B.V.Sc, MRCVS, owner and directory of Farr & Pursey Equine, based in Aldbury, Hertfordshire. Prior to setting up Farr & Pursey Equine in 2015, Rick qualified from Liverpool University in 2006 and worked in equine first opinion practice, alongside Cambridge University and Bishop Burton College. Prior to qualifying as a vet, Ricky completed an Equine Science and Physiology degree at Hull University and has worked within the equine industry acquiring a wealth of equine experience. He is also a qualified BHSAI and NVQ Level 3 assessor.

Ref: Horse & Hound; 14 March 2019