Good yard hygiene practices are vital to help keep infectious disease at bay. Yet no matter how thorough your biosecurity plan, is it sufficiently robust to protect your horses from others that visit your property for lessons or other reasons?

The recent equine herpes virus (EHV-1) outbreak in Hampshire served as a stark reminder of the devastating potential of this disease, when four horses were put down after contracting the neurological strain.

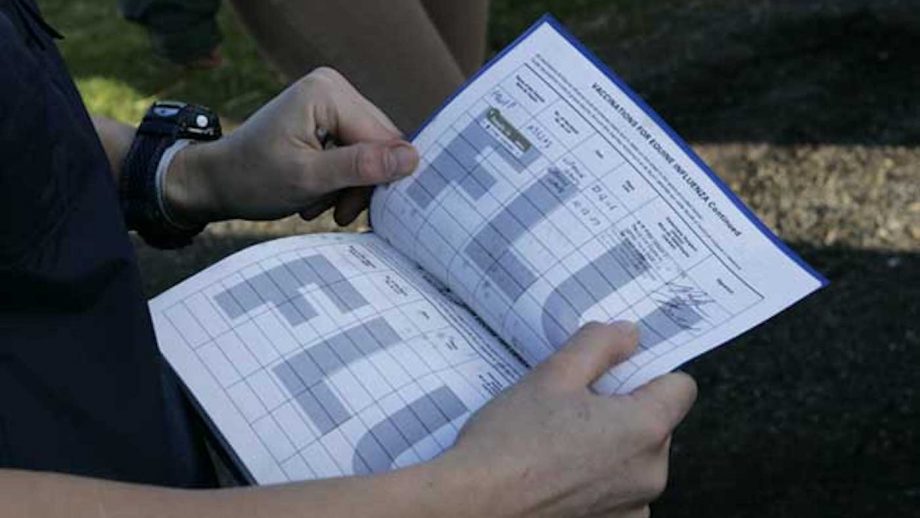

Ideally, visitors to your yard will be scrupulous about their own yard biosecurity, maintaining flu vaccinations and keeping horses at home if there is any suspicion they are unwell. But a seemingly healthy animal may be incubating disease, however, bringing infection through your gates in Trojan Horse style. So what can you do?

{"content":"PHA+V2hpbGUgZXhwZXJ0cyBhZ3JlZSB0aGF0IHlhcmQgbG9ja2Rvd24gKGNlYXNpbmcgYWxsIG1vdmVtZW50IGluIGFuZCBvdXQpIGlzIGV4dHJlbWUgaWYgdGhlcmUgaXMgbm8ga25vd24gaG9yc2UgY29udGFjdCB3aXRoIGFmZmVjdGVkIHByZW1pc2VzLCBpdCBtYWtlcyBzZW5zZSB0byBoYXZlIG9uZ29pbmcgcHJlY2F1dGlvbnMgaW4gcGxhY2Ug4oCUIG5vdCBqdXN0IGFnYWluc3QgRUhWLCBidXQgdG8gbGVzc2VuIHRoZSByaXNrIG9mIG90aGVyIGNvbnRhZ2lvdXMgZGlzZWFzZXMgc3VjaCBhcyA8YSBocmVmPSJodHRwczovL3d3dy5ob3JzZWFuZGhvdW5kLmNvLnVrL3BsdXMvdmV0LWxpYnJhcnkvZXF1aW5lLWZsdS0yLTg2MDA1Ij5lcXVpbmUgZmx1PC9hPiBhbmQgPGEgaHJlZj0iaHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuaG9yc2VhbmRob3VuZC5jby51ay9ob3JzZS1jYXJlL3ZldC1hZHZpY2Uvc3RyYW5nbGVzLWluLWhvcnNlcy0zMDU4MjgiPnN0cmFuZ2xlczwvYT4uPC9wPgo8aDM+QmVhdGluZyBiYWN0ZXJpYTwvaDM+CjxwPkEgZmFtaWxpYXIgY2xpZW50IGFycml2ZXMgYW5kIHVubG9hZHMgdGhlaXIgaG9yc2UgZm9yIHRoZWlyIGxlc3Nvbi4gV2hlcmXigJlzIHRoZSBkYW5nZXI\/PC9wPgo8cD48ZGl2IGNsYXNzPSJhZC1jb250YWluZXIgYWQtY29udGFpbmVyLS1tb2JpbGUiPjxkaXYgaWQ9InBvc3QtaW5saW5lLTIiIGNsYXNzPSJpcGMtYWR2ZXJ0Ij48L2Rpdj48L2Rpdj48c2VjdGlvbiBpZD0iZW1iZWRfY29kZS0zMSIgY2xhc3M9ImhpZGRlbi1tZCBoaWRkZW4tbGcgcy1jb250YWluZXIgc3RpY2t5LWFuY2hvciBoaWRlLXdpZGdldC10aXRsZSB3aWRnZXRfZW1iZWRfY29kZSBwcmVtaXVtX2lubGluZV8yIj48c2VjdGlvbiBjbGFzcz0icy1jb250YWluZXIgbGlzdGluZy0tc2luZ2xlIGxpc3RpbmctLXNpbmdsZS1zaGFyZXRocm91Z2ggaW1hZ2UtYXNwZWN0LWxhbmRzY2FwZSBkZWZhdWx0IHNoYXJldGhyb3VnaC1hZCBzaGFyZXRocm91Z2gtYWQtaGlkZGVuIj4NCiAgPGRpdiBjbGFzcz0icy1jb250YWluZXJfX2lubmVyIj4NCiAgICA8dWw+DQogICAgICA8bGkgaWQ9Im5hdGl2ZS1jb250ZW50LW1vYmlsZSIgY2xhc3M9Imxpc3RpbmctaXRlbSI+DQogICAgICA8L2xpPg0KICAgIDwvdWw+DQogIDwvZGl2Pg0KPC9zZWN0aW9uPjwvc2VjdGlvbj48L3A+CjxwPuKAnEluZmVjdGlvdXMgZGlzZWFzZSBjYW4gYmUgc3ByZWFkIGJ5IGRpcmVjdCBob3JzZS10by1ob3JzZSBjb250YWN0IGFuZCBhbHNvIGluZGlyZWN0bHksIHdoZXJlIGJhY3RlcmlhIGFyZSB0cmFuc2ZlcnJlZCB2aWEgcGVvcGxl4oCZcyBoYW5kcyBvciBjbG90aGluZywgb3IgdGFjayBvciB5YXJkIGVxdWlwbWVudCzigJ0gc2F5cyBSaWNoYXJkIEhlcGJ1cm4gRlJDVlMsIG9mIEImYW1wO1cgRXF1aW5lIFZldHMuIOKAnEVIViB2aXJ1cyBwYXJ0aWNsZXMgY2FuIGxpdmUgZm9yIHNldmVuIGRheXMgaW4gYW4gZW52aXJvbm1lbnQsIGFsdGhvdWdoIGZsdSBwYXJ0aWNsZXMgbWF5IG9ubHkgc3Vydml2ZSBmb3IgdGhyZWUuPC9wPgo8cD7igJxUaGUgZ29vZCBuZXdzIGlzIHRoYXQgYm90aCBhcmUgZWFzaWx5IGtpbGxlZCBieSBkaXNpbmZlY3RhbnQs4oCdIGhlIGFkZHMsIGV4cGxhaW5pbmcgdGhhdCBzaW1wbGUgaGFiaXRzIHN1Y2ggYXMgYSBzcXVpcnQgb2YgYW50aWJhY3RlcmlhbCBoYW5kIGdlbCB3aWxsIGhlbHAuPC9wPgo8cD7igJxNYWtlIHN1cmUgcGVvcGxlIGJyaW5nIHRoZWlyIG93biB0aGluZ3MgYW5kIGRvbuKAmXQgYm9ycm93IHlvdXJzLiBDb21tdW5hbCBob3NlcGlwZXMgY2FuIGhhcmJvdXIgdmlyYWwgcGFydGljbGVzIGFuZCBhcmUgYSBrbm93biBzb3VyY2Ugb2YgaW5mZWN0aW9uIHNwcmVhZCBhdCBzaG93cywgc28gY2xpZW50cyBzaG91bGQgYnJpbmcgYnVja2V0cyBhbmQgaWRlYWxseSB0aGVpciBvd24gd2F0ZXIgc3VwcGx5LiBPdGhlcndpc2UsIGRpc2luZmVjdCB0aGUgaG9zZXBpcGUgZW5kIHJlZ3VsYXJseS48L3A+CjxkaXYgY2xhc3M9ImFkLWNvbnRhaW5lciBhZC1jb250YWluZXItLW1vYmlsZSI+PGRpdiBpZD0icG9zdC1pbmxpbmUtMyIgY2xhc3M9ImlwYy1hZHZlcnQiPjwvZGl2PjwvZGl2Pgo8cD7igJxEaXNpbmZlY3RpbmcgdGhlIHRyYWlsZXIgb3IgbG9ycnkgYWZ0ZXIgZWFjaCBqb3VybmV5IGlzIGFub3RoZXIgc2Vuc2libGUgbWVhc3VyZSwgYWx0aG91Z2ggcmFyZWx5IGRvbmUs4oCdIGFkZHMgUmljaGFyZC4g4oCcV2hpbGUgc2hhcmVkIGVudmlyb25tZW50cyBzdWNoIGFzIGFyZW5hcyBhcmUgdGhvdWdodCB0byBiZSBsb3cgcmlzaywgYSBxdWljayBvbmNlLW92ZXIgd2l0aCBhIGhhbmQtaGVsZCBzcHJheSBkaXNpbmZlY3RhbnQgaXMgd2lzZSB3aGVyZSBhIGhvcnNlIGhhcyBzbG9iYmVyZWQgb24gdGhlIGZlbmNpbmcu4oCdPC9wPgo8aDM+S2VlcCB5b3VyIGRpc3RhbmNlPC9oMz4KPHA+VmlzaXRpbmcgaG9yc2VzIHRoYXQgc3RheSBvdmVybmlnaHQsIG9yIGxvbmdlciwgc2hvdWxkIGJlIHN0YWJsZWQgYSBzdWZmaWNpZW50IGRpc3RhbmNlIGZyb20geW91ciBvd24gaG9yc2VzIHRvIHJlZHVjZSB0aGUgY2hhbmNlIG9mIGRpc2Vhc2UgdHJhbnNtaXNzaW9uLjwvcD4KPGRpdiBjbGFzcz0iYWQtY29udGFpbmVyIGFkLWNvbnRhaW5lci0tbW9iaWxlIj48ZGl2IGlkPSJwb3N0LWlubGluZS00IiBjbGFzcz0iaXBjLWFkdmVydCI+PC9kaXY+PC9kaXY+CjxwPuKAnEVIViBpcyBhIHJlYXNvbmFibGUgc3RhcnRpbmcgcG9pbnQgd2hlbiBjb25zaWRlcmluZyBhbiBpc29sYXRpb24gcHJvdG9jb2wsIGFzIGl0cyBjb25zZXF1ZW5jZXMgYXJlIHR5cGljYWxseSB0aGUgZ3JlYXRlc3Qs4oCdIHNheXMgUmljaGFyZCwgcmVmZXJyaW5nIHRvIHRoZSBwb3NzaWJsZSBwZXJtYW5lbnQgbmV1cm9sb2dpY2FsIGltcGxpY2F0aW9ucyBvZiB0aGUgZGlzZWFzZS48L3A+CjxwPuKAnFdoaWxlIHRoZSBoZXJwZXMgdmlydXMgZG9lcyBub3QgdHJhdmVsIGZhciBieSBhaXIsIGEgZ29vZCBzbmVlemUgZnJvbSBhbiBpbmZlY3RlZCBob3JzZSBjb3VsZCBzZW5kIHBhcnRpY2xlcyBhIGNvbnNpZGVyYWJsZSBkaXN0YW5jZS4gVGhlIGlkZWFsIHBoeXNpY2FsIHNlcGFyYXRpb24gd291bGQgYmUgYXJvdW5kIDMwIG1ldHJlcyDigJQgaW4gYSBzdHJhaWdodCBsaW5lIOKAlCBiZXR3ZWVuIHRoZW0gYW5kIHlvdXIgbWFpbiBzdGFibGUgYmxvY2suPC9wPgo8ZGl2IGNsYXNzPSJhZC1jb250YWluZXIgYWQtY29udGFpbmVyLS1tb2JpbGUiPjxkaXYgaWQ9InBvc3QtaW5saW5lLTUiIGNsYXNzPSJpcGMtYWR2ZXJ0Ij48L2Rpdj48L2Rpdj4KPHA+4oCcVGhlIGJhY3RlcmlhIHRoYXQgY2F1c2Ugc3RyYW5nbGVzIGFyZSBsYXJnZXIgaW4gc2l6ZSBhbmQgYXJlIG1vcmUgb2Z0ZW4gc3ByZWFkIGJ5IGRpcmVjdCBob3JzZS10by1ob3JzZSBjb250YWN0LOKAnSBoZSBleHBsYWlucy4g4oCcRXF1aW5lIGZsdSB2aXJ1cyBwYXJ0aWNsZXMsIGhvd2V2ZXIsIGFyZSBkaXNwZXJzZWQgYnkgY291Z2hpbmcgYXMgYWVyb3NvbGlzZWQgZHJvcGxldHMuIEluIHRoZSAyMDA3IEF1c3RyYWxpYW4gb3V0YnJlYWssIHRoZXkgdHJhdmVsbGVkIHVwIHRvIHR3byBraWxvbWV0cmVzIGJ5IGFpci7igJ08L3A+CjxwPkEgcHJhY3RpY2FsIGNvbXByb21pc2UsIHNheXMgUmljaGFyZCwgaXMgYW4gaXNvbGF0aW9uIHN0YWJsZSBzZXBhcmF0ZWQgZnJvbSB0aGUgbWFpbiBibG9jayBieSBhcyBmYXIgYXMgcG9zc2libGUgYW5kIGZhY2luZyBhIGRpZmZlcmVudCBkaXJlY3Rpb24g4oCUIHdpdGggc2VwYXJhdGUga2l0IGZvciBtdWNraW5nIG91dCwgZ3Jvb21pbmcsIGZlZWRpbmcgYW5kIHdhdGVyaW5nLCBhbG9uZyB3aXRoIG92ZXJhbGxzLCBoYW5kIHdhc2ggYW5kIGEgZm9vdCBiYXRoIGZvciB0aGUgaGFuZGxlciB0byB1c2UgYmVmb3JlIHRvdWNoaW5nIG90aGVyIGhvcnNlcy48L3A+CjxwPuKAnFdl4oCZdmUgcGVyaGFwcyBiZWNvbWUgY29tcGxhY2VudCBhYm91dCBpc29sYXRpb24sIGJ1dCBpdOKAmXMgbm90IGRpZmZpY3VsdCB0byBiZSBwcmVwYXJlZCB3aXRoIHNvbWUgY29tbW9uLXNlbnNlIG1lYXN1cmVzLOKAnSBoZSBhZGRzLjwvcD4KPGgzPldoYXQgdGhlIHByb2Zlc3Npb25hbHMgZG88L2gzPgo8cD7igJxXZSBzb21ldGltZXMgaGF2ZSBjbGllbnRz4oCZIGhvcnNlcyBvbiBzaXRlLCBidXQgbmV2ZXIgZm9yIGFuIG92ZXJuaWdodCBzdGF5LOKAnSBzYXlzIGV2ZW50IHJpZGVyIDxhIGhyZWY9Ii90YWcvd2lsbGlhbS1mb3gtcGl0dCI+V2lsbGlhbSBGb3gtUGl0dDwvYT4uIOKAnEkgbmV2ZXIgdG91Y2ggYSBob3JzZSBpZiBJ4oCZbSB0ZWFjaGluZyBhbmQgSSBkb27igJl0IGFsbG93IHZpc2l0b3JzIHRvIHRoZSB5YXJkIHRvIHRvdWNoIG1pbmUuIElmIGhvcnNlcyBhcmUgY29taW5nLCBwZXJoYXBzIGZyb20gb3ZlcnNlYXMsIHdlIGRvbuKAmXQgd29yayBvdXJzIHdpdGggdGhlbSBpbiB0aGUgYXJlbmEgb3Igb24gdGhlIGdhbGxvcHMuPC9wPgo8cD7igJxJZiB5b3Uga25vdyBzb21ldGhpbmfigJlzIGJyZXdpbmcsIHlvdSBoYXZlIHRvIGtlZXAgdGhlIG91dHNpZGUgd29ybGQgb3V0LOKAnSBhZGRzIFdpbGxpYW0sIHdobyBjbG9zZWQgaGlzIHlhcmQgZHVyaW5nIHRoZSBsYXN0IG1ham9yIGVxdWluZSBmbHUgb3V0YnJlYWsuPC9wPgo8cD7igJxSb3V0aW5lbHksIGR1cmluZyB0aGUgc2Vhc29uLCB3ZSB0YWtlIGV2ZXJ5IGhvcnNl4oCZcyB0ZW1wZXJhdHVyZSBkYWlseSDigJQgd2hpY2ggaGFzIG1hbnkgdGltZXMgYmVlbiBhIGdvZHNlbmQg4oCUIGFuZCBoYXZlIGEgc3RyaWN0IHBvbGljeSBvZiBpc29sYXRpbmcgYWxsIG5ldyBhcnJpdmFscyBpbiBhIHNlcGFyYXRlIGZvdXItYm94IHVuaXQu4oCdPC9wPgo8cD5SZWJlY2NhIEh1Z2hlcywgd2hvLCB3aXRoIGh1c2JhbmQgR2FyZXRoLCB0ZWFjaGVzIHZpc2l0aW5nIHJpZGVycyBhdCBIdWdoZXMgRHJlc3NhZ2UsIGFsc28gcHV0cyBzdHJpY3QgYmlvc2VjdXJpdHkgbWVhc3VyZXMgaW50byBwbGFjZS48L3A+CjxkaXYgY2xhc3M9ImluamVjdGlvbiI+PC9kaXY+CjxwPuKAnE91ciBjbGllbnRz4oCZIGhvcnNlcyBoYXZlIG5vIGRpcmVjdCBjb250YWN0IHdpdGggb3VycyzigJ0gc2hlIGV4cGxhaW5zLiDigJxUaGV5IGFjY2VzcyB0aGUgaW5kb29yIHNjaG9vbCB0aHJvdWdoIGEgc2VwYXJhdGUgZG9vciwgd2l0aG91dCBjb21pbmcgdGhyb3VnaCB0aGUgeWFyZCwgYW5kIHdlIGhhdmUgc2VwYXJhdGUgc3RhYmxlcyA1MCBtZXRyZXMgYXdheSBmb3IgdGhvc2Ugc3RheWluZyBvdmVybmlnaHQuPC9wPgo8cD7igJxXZSBhbHNvIG1vbml0b3Igb3VyIG93biBob3JzZXPigJkgdGVtcGVyYXR1cmVzIGRhaWx5LCBhcyBwYXJ0IG9mIG91ciB5YXJkIG1hbmFnZW1lbnQgc3RyYXRlZ3ksIHRvIHBpY2sgdXAgZWFybHkgc2lnbnMgb2YgaW5mZWN0aW9uLuKAnTwvcD4KPHA+PGVtPlJlZiBIb3JzZSAmYW1wOyBIb3VuZDsgMzAgSmFudWFyeSAyMDIwPC9lbT48L3A+CjxwPgo="}

You may also be interested in…

Library image.

Credit: Lucy Merrell

Library image.

Credit: TI Media

A nasal swab can be used to test a horse for strangles.

Credit: Lucy Merrell

Credit: Lucy Merrell