Sarcoids are the most common skin tumour in horses and ponies and, although they may look like warts, they are locally destructive and are a form of skin cancer.

They are most often found on the abdomen, inside the back legs, around the sheath, on the chest and around the eyes and ears. They also often appear at the site of old scars, particularly on the legs. These are sites where flies typically congregate and insect transmission may be involved in the development of the condition.

Young to middle-aged horses are most commonly affected and there may be a genetic predisposition, meaning horses related to sarcoid-prone animals are more likely to develop the problem. It is a condition that is unique to horses. There is no clear link between colour or breeds of horses being more susceptible.

Sarcoids can appear singly as tiny lumps or in clusters. As they enlarge, the skin may ulcerate and become infected. In summer, they attract flies and can end up as open sores that will not heal.

Sarcoids in horses: Signs | Types | Is it serious? | Treatment | Causes | Prevention

Recognising sarcoids in horses

The appearance of sarcoids can vary considerably. In the early stages they may appear innocuous and are sometimes missed completely if they are concealed within the horse’s coat.

Some sarcoids look like smooth, nodular skin lumps, especially in the early stages, while others are irregular and roughened from the start. The lumps frequently become larger, irregular in shape and cauliflower-like in appearance. Some will ulcerate and become aggressive at which stage they are described as fibroblastic or malevolent sarcoids. Sarcoids can also appear as flat, slightly bumpy areas of skin with a dry, scaly appearance. This verrucose form of sarcoid is sometimes mistaken for ringworm, but it never clears up. Such plaques are often found on the neck, chest and inner thigh. In time, they may develop into other forms of the tumour.

Types of sarcoid found in horses

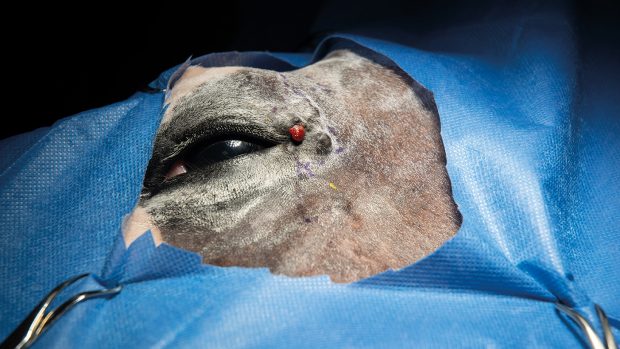

An occult sarcoid beside the horse’s eye prior to treatment.

Occult: a flat patch of hair loss with a grey, scaly surface, which can be confused with ringworm, as they are often circular. Commonly found on the face, neck and between the back legs.

Verrucose: wart-like, grey and scaly but extends deeper than the occult sarcoid. More irregular in outline; multiple lesions often appear.

Nodular: lumps under thin and shiny skin. These vary in size, some being more than 5cm in diameter, and occur commonly around the groin and eyelids.

Fibroblastic: aggressive fleshy masses. They can begin as a complication of a skin wound and sometimes grow rapidly, often ulcerated and “hanging” on a stalk (pedunculated) or extremely invasive into the surrounding skin.

Mixed: a variable combination of two or more types of sarcoid, often of different ages, forming a “colony”.

Malevolent: A term used to describe the most aggressive type of sarcoid. These spread through the skin and even along lymph vessels, with cords of tumour tissue interspersed with nodules and secondary ulcerative lesions. They can become large and difficult to manage.

How serious are sarcoids in horses?

Sarcoids originate from cells called fibroblasts, which play a critical role in wound healing by producing the extracellular matrix and structural proteins that bind the body together. Fibroblasts also produce scar tissue, which is one of the reasons that sarcoids can be so difficult to treat. Most treatments stimulate scar tissue — which exacerbates the problem.

The site of these locally invasive fibroblastic cancer lesions can be troublesome, especially if growths appear in the girth area, groin, in the ear or around the eye. Sarcoids are very likely to recur and can become more aggressive if subjected to accidental or deliberate interference, such as rubbing by tack or failed treatment attempts.

Every single sarcoid should be taken seriously when first detected, as they become more problematic as they enlarge. Where there is one, there is always a risk of others growing elsewhere on the horse’s body. Early treatment is usually most effective, before they become large and more difficult to remove. If you notice a lump on your horse’s skin, it is best to get a vet to check it out.

Horses do not die of sarcoids, but some are put down because the sarcoids become a major nuisance that prevent them from either working or enjoying a good quality of life.

Treatment for sarcoids in horses

Although several treatments are available, there is no magic cure for sarcoids and there is always a high risk of recurrence. Treatment will depend on the position, size and number of sarcoids. Overall the prognosis is poor because of their tendency to recur despite treatment, which can become costly.

Treatment options include:

Surgery: The disadvantage of removing the tumour surgically is that there is a high failure rate – the wound often heals poorly and the sarcoid frequently recurs. If this option is chosen a wide surgical margin around the tumour is important

Ligation: This involves applying a tight band around the base of the tumour. While it will work for some horses, there is a high risk of leaving tumour cells behind to grow back and it can be painful for the horse, especially if the sarcoid is in a delicate area

Cryotherapy: The tumour can be frozen to destroy it, but it often requires repeated lengthy treatments and often general anaesthesia for treatment to be carried out safely

Immune therapy: This method involves injecting the horse with substances, such as BCG, to stimulate the immune system to eliminate the tumour. It can work well for sarcoids around the eye, but several treatments are needed, often under heavy sedation. There is a reported risk of reaction to this treatment, so premedication is routinely given to reduce this risk. There have also been supply problems obtaining the BCG.

Topical treatment: This involves special creams. In the UK a heavy metal preparation was developed by University of Liverpool, while there is also a chemotherapy cream that can be prescribed by sarcoid expert Professor Derek Knottenbelt via his Equine Medical Solutions service. The occult sarcoid pictured above was successfully treated with a combination of Bleomycin Max and Lignaine under Professor Knottenbelt’s direction. Lignaine acts as a local aneasthetic although its use in this situation is to increase the uptake of the active ingredients in the Bleomycin Max to maximise its effectiveness. Results show that the creams work well in some cases, particularly on smaller superficial lesions.

Radiation therapy: This has been shown to be effective. Unfortunately, the danger of radiation makes the treatment expensive and, again, general anaesthesia is required. Radiation therapy is only available at certain specialised centres because of the technical difficulties involved.

Laser removal: A relatively new development, a surgical laser is used to remove the tumour, along with a margin of healthy tissue to reduce the chance of leaving behind any potential cancerous cells, using standing sedation with local anaesthetic or under general anaesthetic. This technique is becoming increasingly widely used.

A small verrucous sarcoid on a horse’s chest before and after lazer removal, showing the large area of surrounding tissue that requires removal.

After surgery the site is typically left to heal by itself from the inside out, usually form a large scab within five to seven days. The extent and location of surgery will dictate the healing rate, but has usually resolved within four to six weeks. Benefits of this treatment include relatively rapid healing time, good cosmetic results with a positive success rate and it can be effective in some difficult anatomical areas, such as the ears.

The lazer surgery site where a small verrucous sarcoid has been removed from the horse’s chest, pictured left 17 days after surgery and right two weeks later.

Whatever treatment option is selected it is essential that treatment is continued until there is an effective response. If treatment is stopped before the sarcoid has been eliminated, there is a strong risk of recurrence, sometimes with a worse lesion than was originally present.

A wide range of home treatments are widely discussed and recommended among horse owners, but vets do not recommend this route. An experienced horse vet once summed this up by asking a client: “If you had been diagnosed with skin cancer by your doctor, would you ask your friend for advice then go online and buy a cream which claims to cure a multitude of aliments, or speak to an oncologist (a doctor that specialises in cancer therapy) and treat the tumours accordingly?”.

How does a horse get sarcoids?

The cause of sarcoids is currently unclear. It is thought that insect transmission may be involved in the development of the skin condition. Research has indicated that bovine papillomavirus1 may involved in the development of equine sarcoids. Strangely the bovine papilloma virus has been found in both sarcoids and normal skin, but a recent study shows there is lower viral load in the normal skin.

Can sarcoids be prevented?

Is it thought there could be a genetic predisposition to the skin condition. Protecting the horse from flies may help. No vaccine is currently available.

Buying a horse with sarcoids

When buying a horse look out for any skin lumps, even if the seller claims they are ‘just a wart’. If you buy a horse with sarcoids, insurance companies will exclude cover for treatment as they are a pre-existing condition and this can prove costly. If you have any concerns, discuss them with your vet.

References and further reading:

1. Association of bovine papillomavirus with the equine sarcoid – May 2003

A pilot study on the use of ultra-deformable liposomes containing bleomycin in the treatment of equine sarcoid – 21 June 2018