Horse colours are a bit like car colours – while we know it’s the “engine” that really counts, there are plenty of riders (and drivers) whose first question is always “what colour is it?” Most horse owners have a favourite colour. Some people love greys, others won’t touch them on account of the grooming demands; there are those that steer clear of all chestnuts believing them to be hot-heads – especially female ones – while others snap them up.

You just have to look round a busy riding school to see how many varieties of colour there are, but in fact there are only two pigment colours of horse hair: red and black, which give three base coat colours: bay, red and black (although some experts add brown to this list). Every other colour derives from these colours – or the absence of colour, which gives you white. Gene modifiers deepen or dilute the colour to give us the vast variety of hues across the equestrian world. Looking at the most common colours, you can see how the bases and pigments work. The range of other coat colours is created by the gene modifiers’ action on these base coat colours.

- Bay: red and black hairs on the coat, with a spectrum from bright to dark bay, with black points. Brown is almost indistinguishable from dark bay, but has no black points.

- Chestnut: red coat without any black hairs. Can vary from light to dark (liver), which is sometimes confused for brown. They have no black points. Their mane and tail may be the same colour as the coat, or a lighter “flaxen” colour.

- Black: black coat with black points. The difference between a black and a dark bay is most obviously seen around the muzzle. A black horse has a fully black muzzle, while a brown or dark bay horse will have lighter hair here.

- Grey: grey horses can be born any colour, and over the years grey out to go white (unpigmented). For example, the famous Lipizzaner horses are born jet black, and most have turned white by the time they are seen in performance. True white has no pigment at all.

- Roan: white hairs mixed with any base coat colour. Roans are distinguished from greys in that they do not go whiter with age, and their heads tend to be a solid colour rather than lightening. Strawberry or red roan: chestnut base coat with white hairs; bay roan: bay base coat with white hairs and blue roan: black base coat with white hairs.

I say tomato, you say tomayto

Like the trousers-pants confusion, Americans use different words to Brits to describe some horse colours.

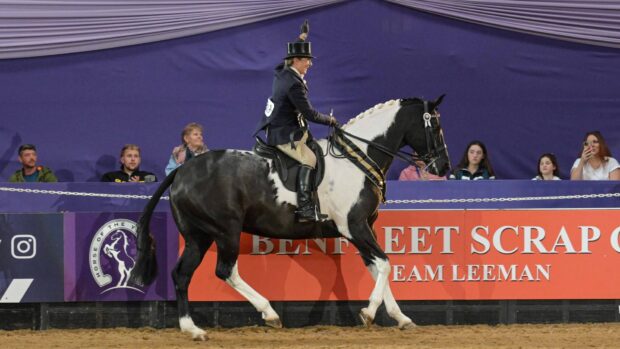

While in the UK, a horse with patches is simply called “coloured” – more specifically piebald for black and white; skewbald for any other colour and white – in the US, they are referred to as pinto. This is sometimes confused with “paint”, which applies to a specific breed of mostly coloured/pinto horses with known quarter horse or thoroughbred pedigrees.

A light chestnut in the UK would be described as sorrel in the US. Chestnut itself was historically spelt chesnut, but nowadays that only applies to the Suffolk horse breed, which is always chesnut (and never any other colour). The word chestnut – whether the seed or the horse colour – did not have a “t” until the early 18th century and remained chesnut in the Suffolk dialect, hence possibly why it is retained for that breed.

Which horse colours: dun or buckskin?

There’s forever a debate about whether a golden horse with black mane and tail should be described as dun or buckskin.

Genetically, they are different. Simply put, buckskin is a bay base colour with one copy of the cream dilution gene, while dun is any base colour with a dun dilution gene. The easiest way to tell the difference without going to the laboratory is via the markings, which are more noticeable in a dun. A dun horse will have a clearly distinct dorsal stripe running down the spine, as well as other primitive markings. Dun horses may have subtle zebra markings on the legs; they often exhibit a shoulder stripe running at right angles to the dorsal stripe; and they may have “frosted” highlights in their mane and tail, rather than pure black. The ear tips may also be darker, and they may show some brown “cobwebbing” on the face. The base coat will affect what sort of dun it is, for example, a blue or mouse dun (called grulla in the US) has a black base coat.

While most people in the UK and Ireland call Connemara ponies of this colour dun, they are technically nearly always buckskin.

While buckskin is a bay with cream dilution, a chestnut base with cream dilution gives a palomino. These range from very light to a deep golden brown, but always with a flaxen mane and tail. Cremello is a chestnut with two cream genes, taking out almost all the colour so the horse is very pale cream. A perlino is a bay with two cream genes, and looks pretty similar to a cremello, though might have slightly darker points. Both cremello and perlino have pink skin and blue eyes.

Most breeds are not defined by their colour, although some, such as the black coat of the Friesian are essential for registration with the breed society. However there are a handful of colour breed registries, such as buckskin, palomino and pinto, where colour is the primary criterion for registration.

White: pure and rare

True white is said to be the rarest horse colour. These horses are born white, unlike most greys, and have a white (unpigmented) coat on pink skin. However, this may be because it is the rarest colour in thoroughbreds, which according to the Jockey Club should be bay, chestnut, black, dark bay/brown, grey/roan, palomino and white. This means it is extremely rare that you find coloured, spotted or buckskin full thoroughbreds, coats that might give rise to extraordinary and rare patterns. White Prince (foaled in US, 2008) is famed as one of the very rare true white thoroughbreds, and could be visited at Kentucky Horse Park. There are very rare instances of coloured racehorses, such as Silvery Moon (foaled in France, 2011), but it is likely that the coloured gene was introduced via a breed or type not too distant from the thoroughbred, such as the Selle Français or Autre Que Pur Sang (AQPS), and therefore they may not be 100% thoroughbred.

There are other extraordinary patterns in other breeds which may actually be rarer, with certain individuals carrying a particularly striking coat. For example, the brindle coat is a rare zebra-like pattern giving the horse a stripy appearance, and an unusual coat texture. Scientists have identified a heritable brindle pattern in a family of American Quarter Horses. The genetics of brindle coats are not fully understood – it is thought to come about largely by chance.

The leopard gene complex can result in spotted horses – although not always. Certain breeds – the Knabstrupper, Noriker and Appaloosa – are associated with leopard genetics, hence their spotted appearance.

And there are yet more colours we could list in the rainbow of a horse’s coat. A simple base of just red, black and bay produces a vast array of myriad hues. What’s your favourite colour?

You may also like to read…

The genetic palette: The science behind coloured horses’ coats *H&H Plus*

Coloured coats tend to be associated with heavy breeding and limited competitive ability – but are the patches allied to

7 things owners of coloured horses and ponies can relate to

A spot-tacular sight: 8 photos of spotted horse and ponies at their annual breed show…

Who reigned in the spot-light?

Subscribe to Horse & Hound magazine today – and enjoy unlimited website access all year round

Horse & Hound magazine, out every Thursday, is packed with all the latest news and reports, as well as interviews, specials, nostalgia, vet and training advice. Find how you can enjoy the magazine delivered to your door every week, plus options to upgrade your subscription to access our online service that brings you breaking news and reports as well as other benefits.