Hundreds of millions have been spent on state-of-the-art equestrian parks at recent Olympics. Horse sport is low priority for the International Olympic Committee (IOC) but, to win a bid, cities with no equine heritage are nonetheless galvanised into acts of largesse.

Invariably, specialist venues become white elephants — Montreal is still paying for 1976 — and there is frustration for leading equestrian nations, who would love to see even a fragment of this investment at home.

Since Athens, though, two factors may end this trend. First, quarantine and re-export issues mean that Beijing 2008 may shift horse sports to the fabulous racecourse facilities in Hong Kong, 1,200 miles away. The change of location — not usually allowed at this stage — could also be political, emphasising Hong Kong’s allegiance to China.

Second, prompted by confirmation that Athens’s final overall cost of €8.95 billion was five times over budget, the Olympic Games study commission says that future host cities must “use existing facilities wherever possible, with new permanent facilities only being built where there is a viable legacy”.

But how often do Olympic horse parks manage to have a viable legacy? And what are the implications of this edict for the future inclusion of horse sports in the Olympics?

The Athens site, at Markopoulo, provided separate stadia for dressage and show jumping, 300 large stables, an aircraft-hanger-sized indoor school and a new cross-country course sculpted among the olive groves. At the 2003 test event, four-times Olympian Andrew Hoy said it was the best facility he had seen. Markopolou far exceeded the FEI’s technical requirements, but its cost had been buried in the budget of the new adjacent Athens Racecourse, which ironically had no Olympic role.

Spyros Capralos, technical director of the Athens Olympics Organising Committee, admitted in 2003 that its cost had spiralled from £160m to £200m, adding, “when it’s the Olympics, you worry about paying for it later”.

Olympic stabling was always earmarked for racecourse use, but the 1,600 leisure horses of mainland Greece never had a hope of sustaining the venue. Greek eventer Heidi Antikatzides has just spent three weeks pursuing racing interests in Markopoulo.

“Maintenance is ongoing and the place is like it was during the Olympics,” she says. “Even the cross-country is intact. It’s still watered and immaculately cut.”

Athens has budgeted 80m a year to maintain redundant venues. It is proposed that private investment will fund their regeneration: Markopoulo will be redeveloped as hotels and conference centres, and the cross-country will become a golf course. Some feel this is a travesty of “legacy”.

Former deputy culture minister Nasos Alevras says: “The venues will remain closed to the public until 2007. On the pretext of making use of them, they are being handed to private companies with a dowry of commercial use and, in some cases, the right to build permanent or prefabricated buildings.”

To horse people, “legacy” implies the creation of a new Hickstead or Aachen. In fact, the IOC wants the wider public to benefit, and in this context the 1996 and 2000 purpose-built parks at Conyers, Atlanta, and Horsley, Sydney, were successful. Both have the busy domestic calendar of a major UK horse show centre, albeit subsidised by conferencing, hotel and “leisure” facilities added later.

As winners of the 2012 bid, London will stage equestrianism at Greenwich using a £6m temporary infrastructure. Some feel Britain warrants a permanent build, but such care over cost may help to save horse sports from the threat of ejection from the Olympics.

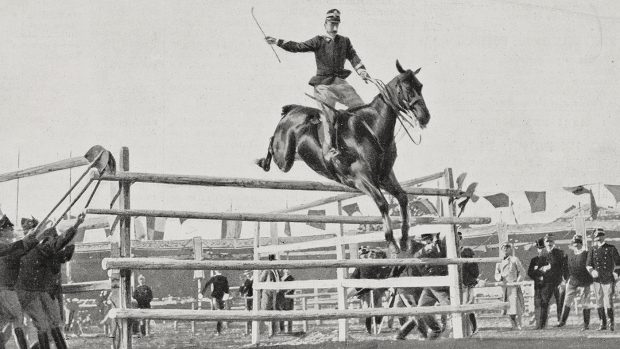

Perhaps one historical lesson is that staging an Olympic sport in a modest way is better than not staging it at all. For London in 1948, the little-known discipline of eventing was held at Aldershot. One spectator, the Duke of Beaufort, was so impressed he launched an annual three-day event at Badminton. Do legacies come any better?

Who staged what and where

1984: Los Angeles

Arena disciplines at Santa Anita Racecourse. Cross-country at ranch of Douglas Fairbanks jnr. Cost: undisclosed. What happened next: Cross-country taken down. Santa Anita remains California’s main racecourse, hosted 2003 Breeders’ Cup.

1988: Seoul

“Grand Park” at existing racecourse. Cost: undisclosed. Afterwards: no equestrianism. Racing interests progressed with 32,000 capacity grandstand built in 1992.

1992: Barcelona

Arena disciplines at Real Polo Club; cross-country at Ballasteros family estate. Cost: £22m. Afterwards: polo club flourished; cross-country became golf course.

1996: Atlanta

Purpose-built Georgia International Horse Park. Cost: undisclosed. Afterwards: training and show centre at national level; leisure amenities, golf, housing.

2000: Sydney

Purpose-built Horsley Park. Estimated cost: £40m. Afterwards: training and show centre, mostly at national level; some FEI dressage and eventing; “family” leisure facilities.

2004: Athens

Horse park bolted on to new racecourse at Markopoulo. Cost: £200m (including racecourse). Afterwards: racecourse absorbed Olympic stabling. Occasional show use. Planned redevelopment for hotels/leisure.

|

||

|

||

Get up to 19 issues FREE

Get up to 19 issues FREE TO SUBSCRIBE

TO SUBSCRIBE