The belief that war horses are no longer used in battle is not entirely true. The first evidence of horses in warfare dates back to some time around 1500–3000BC, with warriors fighting on horseback from around 900BC. And while battle cavalry was a still crucial element of the Napoleonic Wars and the American Civil War in the 19th century, by the 20th century, more mechanic forms of attack began to prevail.

By World War I, horses were no match for tank warfare, and around eight million horses died – nearly half a million of them British. More hearteningly, British Army Veterinary Corps successfully treated over half a million horses during the World War I. A few cavalry units were still in action in World War II. However, they were more commonly used for transporting supplies and troops rather than the previous role in the thick of battle as chargers.

While horses have no place in modern Western warfare – as witnessed in Ukraine – in developing countries, they are still used by armed fighters, and indeed the US Army special forces used local horses in battle in the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan. However, for the main part, mercifully, a “war horse’s” role is reserved for historical reenactments, mounted patrol and ceremonial or educational purposes.

‘War horses’ are now more commonly seen as part of history re-enactments

What breed is a war horse?

War horses came in many shapes and sizes, and were allocated roles according to their physical capabilities. Much like the men who were conscripted to fight, civilian horses that were fit and strong enough to help fight the cause were enlisted. We are familiar with the sight of a relative lightweight breed as war horses – similar to a thoroughbred/warmblood, but this is probably due to the fact that the most famous ones were ridden by the noblemen, such as the Duke of Wellington’s Copenhagen, and therefore commemorated forever as statues.

The heavier draught horses, such as Percherons, Friesians, Shires and Clydesdales, were used for pulling wagons with cannons or artillery, or transporting troops and supplies. These colder-blooded horses were more disposed to remain calm in battle with the noise of gunfire. Joey, the fictitious war horse from the eponymous book by Michael Morpurgo, was this sort – a plough horse who was used to pull carts with wounded soldiers and infantry guns.

Middleweight horses – similar to the modern warmblood – were used both to pull wagons and to carry heavily armoured soldiers in battle, but they lacked the speed and endurance of the lighter cavalry. They were also used for reconnaissance missions, supply, raiding and communication.

The lighter, faster types, such as thoroughbreds, Arabs, Barbs and Akhal Tekes were used for cavalry charges and warfare requiring speed, endurance and agility. Because these breeds are not weight carriers, their riders typically carried little armour and used lightweight weapons such as bows, spears and rifles.

Recent research has show that medieval war horses were more likely to be pony-sized, with horses of 15hh and above actually very rare. Researchers also said it is likely that throughout the medieval period, different conformations of horses would have become desirable in response to changing battlefield tactics and cultural preferences.

A Cavalry Black in ceremonial dress for a military funeral

Horses in the modern day Household Cavalry can be a variety of breeds, usually Irish Draughts (and crosses), but can also be Cleveland Bay, Fresian or warmblood. The ‘Cavalry Black’ refers to any black horse that meets the required height and conformation standards set by the Household Cavalry Mounted Regiment.

Cavalry riders and their war horses resting on their way to a battlefield in 1916

Horses in World War I

At the start of WWI, many horses were enrolled as part of the cavalry, and the British Army entered the war with 25,000 horses at their disposal. They purchased a further 115,000 under the compulsory Horse Mobilisation Scheme, which involved acquiring horses from domestic and international sources.

As the horses were so vulnerable to modern machine gun fire, by the end of the war their role was more about transporting troops and ammunition. Military vehicles were relatively new at this time, which meant that horses and mules were seen as a more reliable and accessible form of transport. Thousands of horses were used to pull field guns – but with up to 12 horses required to pull each gun, exhaustion was a real problem.

Around 484,000 British horses died in World War I, which is one for every two British soldiers. The largest single day of loss occurred during the Battle of Verdun in 1916, with 7,000 horses killed by long-range shelling and single shots.

A German vet treats a French war horse wounded by an aero-bomb in France, circa 1917

Vets treated 2.5m horses during World War I – of these, 2m recovered and were returned to the battlefield, but it could take carers up to 12 hours to clean a horse and its harness after battle.

Much to the relief of British horse owners, due to advances in mechanisation there were far fewer horses needed by the British Army in WWII. In 1942, the British employed 6,500 horses, which was a small figure compared to the 2.75 million and 3.5 million used by the German and Soviet armies.

Famous war horses

Like comparing Arkle with Best Mate, it’s invidious to compare the best of a generation across the decades, or even centuries. However, there are a handful of war horses who go down in the annals of greatness.

Statue of Duke of Wellington riding Copenhagen at Hyde Park Corner in London

Copenhagen

The Duke of Wellington’s chestnut charger in the Napoleonic Wars. The Arab/throroughbred was named for the second battle of Copenhagen, won by the British. His day of days (and consequently the whole nation’s) came on 18 June, 1815, during the Battle of Waterloo, when Wellington’s main opponent, the French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, was defeated.

Copenhagen was extremely well-bred for the racetrack (though he won only two races), with both his grandparents (Eclipse and John Bull) being Derby winners. Copenhagen enjoyed a happy retirement at the Duke’s Hampshire estate until his death at 28, and apparently had a penchant for sponge cakes and chocolate creams. He was honoured with a full military funeral.

An Arabian stallion called Marengo was Copenhagen’s opposite number, ridden by Napoleon – but as he was captured by the Brits in the Battle of Waterloo, Copenhagen gets the nod.

Warrior was the horse that “the Germans couldn’t kill”

Warrior

General Jack Seely’s aptly named charger in World War I was dubbed the horse the Germans couldn’t kill on account of the number of misses he survived.

Warrior eventually died at the age of 33, having carried his master safely through four years of war, from Ypres to the Somme, Passchendaele and Cambria, finally leading a cavalry charge which crucially checked the great German offensive in the spring of 1918.

Jack Seely writes in his book, Warrior: The Amazing Story Of A Real War Horse, “In the War nearly all Warrior’s comrades were killed, and nearly all of mine, but we both survived, and largely because of him.”

Statue of Alexander the Great and Bucephalus in Edinburgh

Bucephalus

The favourite horse of Alexander the Great, one of the most famous generals of antiquity. Legend has it that a 13-year-old Alexander was gifted the horse and he later accompanied him in many battles, with the horse eventually being killed in the Battle Hyadspes River in 326BC.

To honour the horse, Alexander built a city named after Bucephalus in what is now Pakistan.

Sergeant Reckless is fed cake by the wife of Lt. Eric Pederson during a Marine Corps event at which the mare was guest of honour

Sergeant Reckless

Unlike the speedy chargers with mostly thoroughbred blood, Reckless was a Mongolian mare used by the US Marine Corps in the Korean War in 1952.

Centuries earlier, Ghengis Khan and his soldiers conquered lands from Hungary to Korea riding Mongol horses, so this small, durable breed is no back number in the battle field.

Reckless would transport supplies and evacuate soldiers, continuing despite being injured twice. She was so named for her fearless nature, and was given the rank of Sergeant in 1954 having conducted 51 solo rides in one day. She amused the unit with her liking for scrambled eggs and beer.

A modern-day ‘war horse’

The modern event horse has very recent roots in war horses. From 1912 to 1948, all eventing competitors were male, rode in military uniform and were commissioned officers. Only in 1964 were women allowed to compete – the concept hitherto being that if the cross-county mirrored a battle field, an injured soldier would continue (thereby not letting down his country – or his team), whereas if a female rider fell off her male team-mates would not expect her to continue.

Some riders, including Vittoria Panizzon, still present their horses and compete in miltary uniform

Eventing was often referred to as “the military” in its early days, when the competition served as a the complete test of an officer’s battle charger. The dressage signified the horse’s ability to perform ceremonial parades and show obedient training in formation; the cross-country tested speed, endurance, and boldness as they would need in battle, while the showjumping showed if a horse was sound after “battle” and could recover well enough to perform a simple jumping test.

Olympic silver medal winning event horse Toska was later ridden into battle during WWII

Many eventers in the early part of the 20th century were real-life war horses. Seweryn Kulesza won a silver medal as part of the Polish eventing team riding his horse Tóska at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. A few years later, he rode this same horse as his battle charger in World War II, when the mare was killed, Seweryn was captured by the Germans and spent the rest of the war in Oflag VII-A Murnau prisoner-of-war camp.

Of all the horses competing in Olympic disciplines, eventers – typically near thoroughbred, or lightweight warmbloods with a high percentage of thoroughbred – show the closest link to the battle chargers that fought on behalf of his country or territory over millennia.

You may also like to read…

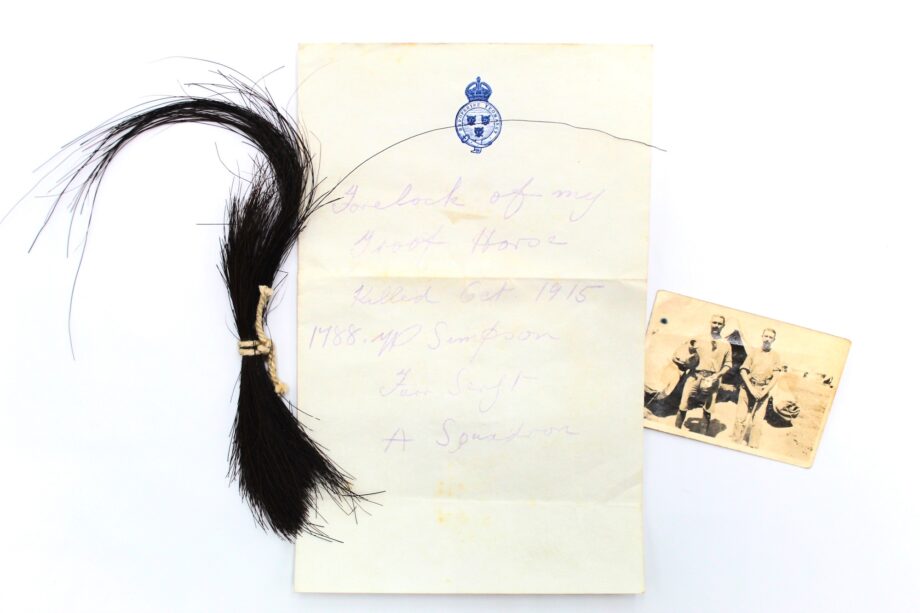

‘A bond broken by death’ but enduring for 100 years: forelock of horse killed in war saved by his soldier for decades

‘Massive and powerful’ medieval warhorses thought to only be ‘pony-sized’, says new research

‘Past, present and future’: life-sized equine sculptures honour fallen horses of World War I

The site was previously a remount depot and horse hospital, supplying the military with horses for operational use from 1904.

Subscribe to Horse & Hound magazine today – and enjoy unlimited website access all year round