“Swimming against the tide,” is how Sue Devereux MRCVS describes her early experience as a veterinary acupuncturist.

“I was trying to tell people that it’s not just a case of sticking a few needles in,” explains Sue, who was one of the first UK vets to establish an equine acupuncture referral practice around 15 years ago. “Gradually, clients wanted it for their horses — and vets slowly started to get used to it. The past three years have seen a massive acceptance within veterinary practices.”

Sue’s interest was ignited when acupuncture achieved what conventional medical treatment couldn’t: relieving the severe neck pain she was suffering due to a long-standing riding injury. Yet, while 2.3m acupuncture treatments are carried out on humans in the UK each year, according to the British Acupuncture Council, we’re still behind when it comes to horses.

“Acupuncture is an established part of sports horse medicine in the USA and many European countries,” points out Sue, whose patients include Olympic athletes alongside general riding horses and racehorses. “I believe it will become a fully integrated part of veterinary medicine here, too, instead of being viewed as a complementary therapy.”

So what can acupuncture do — and how is it developing from a last-resort consideration to a first line of defence in treating and managing a whole host of equine conditions?

Getting the needle

The use of acupuncture within traditional Chinese medicine can appear somewhat mystical. It’s easier to grasp an understanding of its adaptation for Western medicine, to alter nerve and muscle function and promote natural self-healing.

“Inserting acupuncture needles stimulates tiny nerve endings that carry impulses to the spinal cord and brain,” says Sue. “Responses within the nervous and endocrine systems lead to the release of neurotransmitters and hormones, which influence the function of body tissues and organ systems.

“Natural painkillers, such as endorphins, enkephalins and serotonin, can then act on pain pathways — effectively modulating the transmission of incoming pain signals.”

According to Sue, acupuncture is effective for musculo-skeletal and medical conditions including digestive, respiratory and reproductive problems.

“It can stimulate the immune system, perhaps if the horse is lethargic or post-viral, and offers a pain-relieving alternative if a horse cannot have bute or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatories [NSAIDs],” says Sue. “There are just three things it cannot be used for: irreparable fracture, terminal organ failure and malignant tumours.”

While often used as a stand-alone treatment, acupuncture is particularly effective in combination with conventional veterinary medicine. “It can speed up recovery and reduce the amount of medication needed, which is important for horses competing under FEI or racing rules,” says Sue. “Horses receiving acupuncture before or during competitions must be properly examined. Acupuncture should never be used to mask pain, in case serious injury occurs.”

Acupuncture using needles can only be practised by qualified vets who have had specialised training.

“The horse has the same clinical work-up,” says Sue. “I consider the horse’s history before carrying out a full clinical exam. This includes palpation to feel for swelling, heat, pain or tension, and interpreting sometimes very subtle responses such as a pause in his chewing or a change in his eye. I like to see him lunged, turned in tight circles and ridden, if appropriate, as well as inspecting his teeth and his tack.

“Ideally, this examination takes place in his home environment,” she adds. “I can then check the things you’d miss at a clinic, such as his demeanour and posture at rest and at home, his management and even the fit of his rugs and the quality of his hay. It’s a holistic, whole-horse assessment, not just ‘What’s wrong?’, but ‘How did it get like that?’”

Hitting the target

Based on these findings and her knowledge of veterinary anatomy and physiology, Sue selects acupuncture points.

“The needle locations are close to bundles of nerves and blood vessels that act as ‘doorways’ to the nervous system,” she says. “For a hindlimb problem, for example, I might place a needle close to the area of the spine where the nerves that supply that area originate.

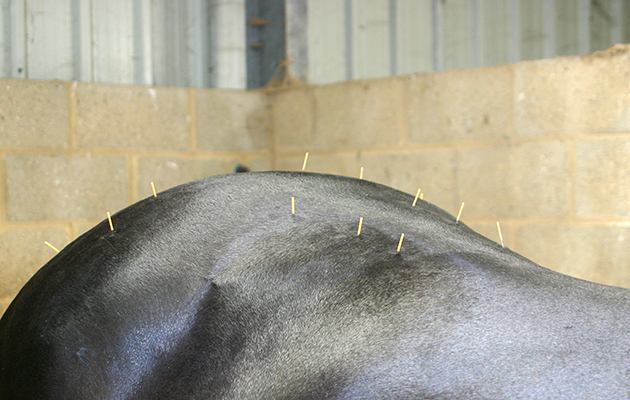

“Needles are generally left in for around 15-20 minutes, shorter for an acute injury and longer for a chronic problem. In some cases the horse displays good relaxation in seconds, especially with tight, tense back muscles. A chronic injury may need several sessions before you see improvement, although there is usually a response after one or two.”

Sue starts with “dry needling”, using sterile, stainless steel needles. If the response could be better, she may use “electroacupuncture” — where a pulsating electrical current passes through the needles.

“Electroacupuncture produces greater activation of descending nerve pathways, from the brain to the injury, to block pain,” she says.

Some horses are notoriously needle-shy, so how do they cope?

“Acupuncture should not be stressful for horse, owner or vet,” says Sue. “Generally the horse is calm and relaxed after gentle palpation. Some acupuncturists don’t like to put a needle into a very sore area, but this can be really effective. In this situation I insert one needle at a time.”

Sue briefs the owner about safety and prefers working in an empty stable with rubber flooring, to avoid the needle-in-a-haystack search should one go missing.

“In experienced hands, acupuncture is very safe,” she adds. “Side effects are far less common than with many conventional forms of medication.

“There is risk of infection at the needle site, but this is incredibly rare. Nevertheless, I would never insert a needle into a joint or a tendon sheath. If there are any safety doubts I use laser acupuncture, which does not penetrate the skin.”

Where’s the evidence?

Sceptics may highlight the lack of scientific proof behind equine acupuncture, yet Sue points to growing evidence in human research.

“With horses, response to treatment is the measure of success,” she says, explaining that randomised trials with animals are tricky for reasons of funding, logistics and welfare.

“Our understanding of the brain and nervous system is increasing all the time, but is far from complete,” adds Sue, who recently submitted a paper to a scientific journal regarding electroacupuncture in the management of trigeminal mediated headshaking, a small study returning “really encouraging results”.

“If a horse is stiff or sore, and hasn’t been helped by vet treatment or rest, acupuncture is well worth considering.”

Ref: Horse & Hound; 2 February 2017