The equine alimentary tract starts at the mouth and finishes at the anus. As in all animals and humans, this tubular passage has an essential role in the digestion of food and the elimination of waste. Because the horse is herbivorous, different parts of his alimentary tract are specialised and adapted to dealing with an exclusively plant-based diet.

The large intestine, which includes the caecum, colon, rectum and anal canal, is the final section of the alimentary tract and vitally important in the digestion of roughage (the fibrous parts of grass and other plants, which includes cellulose). This is also where useful nutrients and water are extracted, which the body absorbs into the bloodstream and subsequently uses for energy, growth, repair and reproduction.

The digestion of fibre is undertaken in the large intestine by a process that involves fermentation by symbiotic (helpful) bacteria. For this reason, horses are known as “hindgut fermenters”. This is different from other herbivorous animals such as ruminants (cattle, for example), which are foregut fermenters and have larger and more complicated stomachs where this process occurs.

The major areas where fermentation takes place are the caecum and the large colon.

The caecum is a roomy fermentation “vat” that is blind-ending (closed at one end) and can accommodate 20 litres or more of ingesta (food). The large colon — also known as the ascending colon — is a long, wide tube connecting the caecum to the rectum.

Bacterial fermentation in the large intestine produces volatile fatty acids (VFAs), which are absorbed across the lining of the intestine into the bloodstream. These chemicals serve as an important source of energy for the horse; indeed, it is estimated that VFAs supply well over 50% of the horse’s energy requirements.

Bacteria and other microorganisms in the large intestine also synthesise vitamin K and water-soluble vitamins, which are absorbed as nutrients. The large intestine also absorbs copious amounts of water and electrolytes (salts) from the intestinal contents, a process that is critical for water and electrolyte balance.

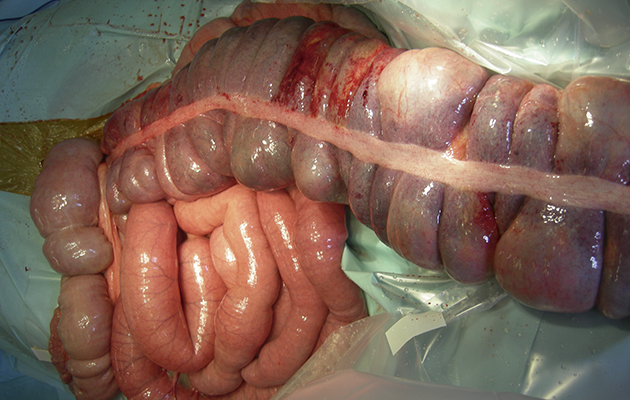

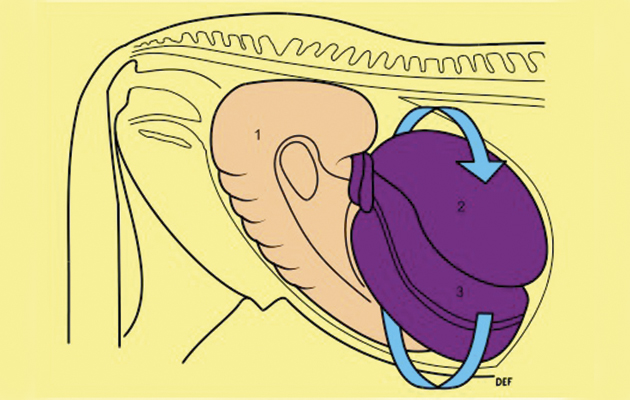

The lengthy and capacious large colon can accommodate 80 or more litres of ingesta. It is folded into two horseshoe-shaped lengths of intestine, one sitting on top of the other, with the “toes” of these shoes pointed towards the horse’s head.

The large colon starts on the right-hand side of the abdomen, next to the caecum, and finishes on the same side — above the starting point but closer to the backbone. With the exception of the beginning and end of the tube, most of the large colon is potentially free to move within the abdominal cavity.

A movable feast

The complex functions of the large colon, plus its huge size and mobility, make this part of the gastrointestinal tract prone to malfunction, displacements and twists.

Infection is one danger, from a variety of bacteria, including salmonella and clostridia, from viruses such as rotavirus and coronavirus, and parasites such as small redworms (the cyathostomins). These can invade the large colon and multiply within it to cause colitis — severe damage and inflammation of the intestinal wall.

Since the large colon is so sizeable, with such an extensive surface area, damage to the wall lining can result in life-threatening disease.

In adult horses, colitis usually results in diarrhoea and weight loss. Affected horses can rapidly become shocked and dehydrated, due to the passing of vast quantities of water and electrolytes in the diarrhoea.

In addition, damage to the intestinal wall allows bacterial toxins (such as endotoxins, which are the components of the cell walls of certain bacteria) to pass through into the bloodstream. This exacerbates the shock and can cause serious damage to other vital organs. Endotoxins are usually found on the inside of the intestines, mixed with the ingesta, but in a healthy horse the intestinal wall prevents them from gaining access to the bloodstream.

For all of these reasons, diarrhoea in adult horses must be treated as a serious and potentially fatal condition that requires intensive treatment (usually in a hospital).

Horses are prone to developing mild diarrhoea for many other reasons, of course, such as nutritional change. Being turned out onto fresh grass is a likely culprit, but in these cases the lining of the intestine remains healthy and the diarrhoea is not severe.

Diarrhoea of a “cowpat” consistency is less likely to be serious than watery diarrhoea. If there is no obvious nutritional cause for it, however, do not assume there is no underlying disease that needs investigating and treating. If in doubt, consult your vet.

Twists and turns

One of the by-products of fermentation is gas. The large amount of round-the-clock bacterial fermentation taking place within the large colon means that horses produce copious quantities of gas.

Gas can build up in the intestine, however, and distend it like a balloon. As in humans, this trapped wind is painful and can result in colic (known as gas or tympanitic colic). While this is most likely to happen when horses eat highly fermentable roughage, such as fresh green grass, some individuals are prone to suffering from gas colic regardless of their diet.

Distension of the intestine with gas can also make it unstable, so that it starts to “float” inside the abdomen.

This instability, coupled with the mobility of most of the large colon, means that it can shift into abnormal positions (known as displacements) and/or twist (called a torsion, or volvulus).

There are various different positions that the large colon can adopt when it becomes displaced, such as left or right dorsal displacement, but the effects are broadly similar — the displaced intestine is blocked and the wall is stretched due to distension, resulting in pain and colic.

Some displacements resolve with medical treatment and dietary management, but others may need surgery to empty out the distended intestine and return it to its normal position. In either case, close veterinary attention is essential.

Torsions of the large colon are potentially much more serious. If the colon twists through more than 360º, it will strangulate — that is, the blood supply to the twisted part is cut off, resulting in death of the affected section.

Strangulating colon torsions are most commonly seen in broodmares soon after foaling, possibly because the colon is able to move into the additional space vacated by the foal and twist. They can occur in other horses, however, and usually result in severe colic pain. Without immediate surgery, death can occur within hours.

Ref Horse & Hound; 8 December 2016