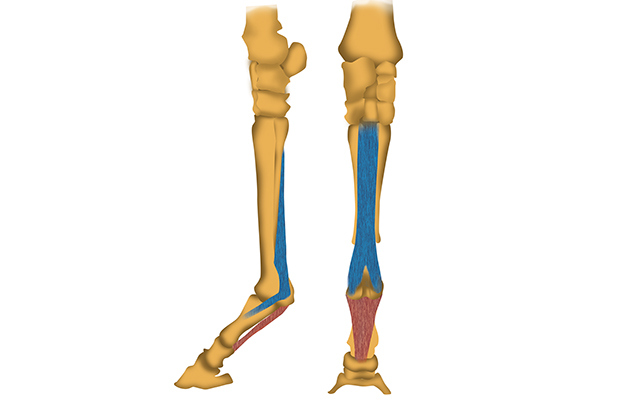

Both front and hind limbs have a suspensory ligament, which runs down the back of the leg parallel to the cannon bone (see diagram, below).

In the forelimb, the top of the ligament is attached to the back of the cannon bone, just below the knee, with a small accessory branch attaching to the back of the lower bones of the knee. In the hindlimb, the ligament starts at the back of the hock, with one part attaching to the back of the fourth tarsal bone (within the hock joint) and a second, larger part attaching to the back of the cannon bone below the hock.

From the mid-cannon region, the ligament splits into two branches, which continue down to the level of the fetlock joint where they attach to the proximal sesamoid bones.

The suspensory ligament acts to support the fetlock when the limb is loaded. Considerable strain is placed upon it as the fetlock is extended (drops), particularly when the hock is flexed (or the knee is extended) at the same time. It is not surprising that horses with injury to the hind suspensory ligament can also have associated hock pain.

Made up of strong ligament/tendon tissue, surrounding a mixture of muscle and fat, the ligament is packed with tiny nerves and blood vessels. A sudden-onset single injury — or, more frequently, repetitive overload — can result in tearing of ligament fibres or disruption of the muscle, fat, nerve or vascular tissue.

Suspensory desmitis (inflammation and damage to the ligament) or suspensory desmopathy (a more degenerative type of damage) can occur at all levels of the ligament, or in the cannon bone or proximal sesamoid bones in the attachment areas.

Damage at the bone/ligament interface sometimes results in a bone reaction or attempted repair, where the ligament pulls repeatedly on its bony attachment, or in an “avulsion fracture” where a small piece of bone may be pulled off at the ligament attachment.

The origin (top) of the suspensory ligament is prone to injury, known as “proximal suspensory desmitis”, often as a result of repetitive overloading. Dressage horses are particularly at risk from damage to the hindlimb origin. In a survey of affiliated dressage horses, 25% had experienced pain associated with the hock or suspensory ligament.

Damage to the body of the ligament usually occurs as an extension of injury from its origin or branches. A single branch can be injured, often due to imbalances in loading patterns through the limb, or a pair.

Danger signs

Swelling, heat or pain around the ligament — even if the horse is not showing obvious lameness — may be the first sign of damage to the suspensory ligament body or branches.

These signs may be quite generalised, or appear as slight thickening or enlargement behind the cannon bone or above the fetlock.

Horses with lameness but without heat or swelling may have ligament scarring or degeneration. Damage to a splint bone can also result in damage to the adjacent suspensory ligament.

Proximal suspensory desmitis (or desmopathy) can lead to swelling, heat or pain on pressure, but more often a horse will show signs of pain through lameness or poor performance. Lameness can have gradual or sudden onset, but injury is most frequently detected because of a subtle alteration in gait quality, or the horse’s resistance or reluctance to “sit” or perform specific movements on one or both reins. Pain from proximal suspensory desmitis can lead to conflict behaviour, where a horse becomes confused about being asked to perform a movement that he associates with pain. To avoid the situation he may stop, twist, resist the contact, wave his head, or even buck or rear.

If swelling or pain is present, the injured area is easily identifiable and diagnosis can be straightforward. Without obvious signs on the leg, identification of the site of lameness can be more challenging, particularly where it has to be separated from a suspected training problem.

Nerve blocks can pinpoint the site of pain, so that imaging methods can be used to identify the problem. While X-rays can give information on severe or long-term bone damage, ultrasound is the mainstay for evaluating the suspensory ligament and surrounding structures. Scintigraphy (bone scanning) can give data on whether bone damage is active, but MRI generally provides more detail on the degree and activity of damage in the ligament and the bone at its attachments.

What’s the prognosis?

While early detection and treatment of injury can lead to good recovery, some cases of long-term or severe damage can be frustrating to treat and difficult to manage.

Bone injury at the ligament attachment is often successfully treated with rest and a controlled exercise programme. Injuries to the branches can be treated a bit like tendon injuries, with initial treatment of the inflammation followed by a controlled exercise programme. Injecting medication or biological agents, including stem cells, may be required and there is indication of potential success with a new form of laser treatment.

Proximal suspensory injury can be hard to treat, particularly in the hindlimbs. Young horses with early or subtle forelimb suspensory injury can benefit from rehabilitation, which comprises core muscle development and improved back flexibility along with controlled exercise and a review of the training surface. Response to conservative treatment can be poor in horses with longer-term injury or with a clearly defined core lesion, however, with less than 20% returning to work successfully. Laser treatment or injection of specific medications into the “hole” to encourage healing can be useful.

In cases that do not respond, or with more chronic hind suspensory injury, surgical treatment may be required. This can include resection of the tight band of tissue around the ligament to aid repair and/or resection of nerve supplying this area of the ligament.

Of carefully selected cases, a reported 78% can return to full work one year post-operatively. Horses with other concurrent reasons for lameness are less likely to do well; only 44% were in full work a year later, in the same review.

Risk factors

Conformation: It has been suggested that horses with straight hock (and dropped fetlock) conformation are more likely to suffer suspensory ligament injuries — probably because this conformation makes the horse more likely to hyperextend the fetlock during normal locomotion and place greater strain on the ligament.

Movement: Extravagant movers tend to flex their joints and extend the fetlock, which could put more strain on suspensory ligaments. The more “uphill” a horse appears, the greater the strain likely to be experienced by the hind suspensory ligaments in trot.

Training: Being asked to perform and repeat movements without adequate muscle strength or endurance, flexibility or fitness can result in the horse using incorrect muscle patterns. Parts of the body are then overloaded to compensate for the weakness, leading to abnormal strain on the lower limbs – including the suspensory ligaments.

The “bigger” (the faster or more extended) the trot, the more the fetlock drops and the greater the strain on the ligaments. Training talented horses in extravagant trot or canter movements when they lack the strength and fitness to support this increases injury risk.

Careful management and intelligent training can minimise risk. Cross-training and core muscle development are vital, as is avoiding over-repetition of exercises when a horse is tired. Over-producing or over-pushing extravagant paces is not recommended, particularly in young horses or those with poor core muscle strength.

Ref Horse & Hound; 13 October 2016