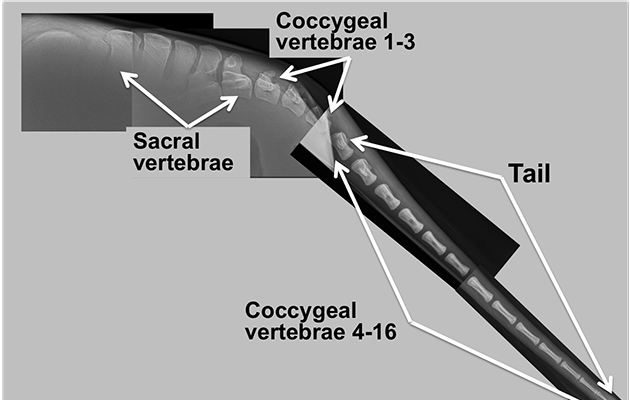

The rear section of the equine spine comprises an average of 18 coccygeal vertebrae, which taper to a point at the end of the main body of the tail — the fleshy part commonly called the dock.

Cushioning intervertebral discs allow this strong but very flexible structure to move in all directions. One set of paired muscles on top of the tail head are used to elevate the tail, while a second set below can clamp it down. A combination of these muscles creates side-to-side motion.

The equine spinal cord finishes just before the dock at the first to second sacral vertebra, petering out into a thin, fibrous cord that extends to the fourth sacral segment. Together with the sacral and caudal spinal nerves, these cord endings form the cauda equina — the function of which is to provide motor nerves to part of the hind limbs, the anal sphincter and the tail muscles, plus sensory nerves to the skin of the rump and perineum. The cauda equina also controls the bladder and rectum.

Potential problems

Injury to the sacrococcygeal region is rare but can result from the horse falling over backwards and landing on his tail. Damage can also occur if he sits down or backs into an object, either suddenly or for an extended period.

Excessive pulling on the tail, perhaps while turning a horse cast in his stable, can also cause problems. This is a greater risk to foals, however, because of the large amount of force required to cause injury in an adult horse.

Tail fracture is uncommon but typically involves the first or second coccygeal vertebra. Fractures are usually closed, with no broken skin, and frequently malaligned. Localised pain and instability are often present, with more chronic cases featuring bony enlargement, hair loss, muscle atrophy and reduced tail mobility. Diagnosis is made by physical palpation and is easily confirmed by X-ray.

Treatment involves anti-inflammatories and rest to limit excessive tail movement. If the horse is unable to extend his tail then he may also struggle to defecate, causing an accumulation of droppings within the rectum. Fracture union can be a slow process, with malalignment often resulting in permanent deformity such as a clamped or wonky tail.

A normal tail will have a full range of movement. Excessive swishing is sometimes seen by riders as a sign of resistance and can occur with a variety of conditions that affect

the horse’s willingness to exercise. This is not associated with any particular problem from a veterinary perspective, but can be used as part of a response assessment during the work-up of an individual horse.

A flaccid tail is of greater concern, as this implies altered neurological or muscle function, or both. A thorough neurological examination is then required to identify any extensive neurological deficits and to define their cause.

Trauma to the tail area can also result in damage called cauda equina — the term for damage to this complex structure, as well as for the cord and nerves at the very end of the spinal cord. Depending upon its location and severity, this damage can lead to tail weakness or paralysis and atrophy of the muscles of the tail head. Anal tone or skin sensation around the perineum and tail may be reduced or absent. The horse may struggle to empty his rectum and suffer urinary incontinence, becoming unable to retract his penis into its sheath. With mares, urine may pool in the vagina.

Occasionally, hindlimb weakness or incoordination and atrophy of the gluteal muscles may also be present. The prognosis for coccygeal trauma is variable, depending upon the degree of tail dysfunction. If cauda equina is present, however, the outlook is invariably poor.

Testing times

The tail pull test is an important part of the equine neurological examination and should be performed in any case with altered tail function. The tail is held out to the side and pulled progressively — not yanked — using the examiner’s bodyweight alone, which does not cause any damage. The test is performed in two stages, standing and walking, on both sides, with the aim of identifying two types of weakness.

The standing stage tests the function of the hindlimb muscles and their spinal reflex arc (the communication mechanism that stimulates contraction). Standing weakness is termed lower motor neuron paresis. In addition, the walking stage also tests the function of the neurons that relay positional information to and from the brain. Walking weakness, without standing weakness, is termed upper motor neuron paresis.

Horses that are weak at rest will also be weak when walking. Coordination tests are then used to locate the neurological problem.

Bandage danger

An overly tight tail bandage can cause avascular necrosis (death of bone tissue due to lack of blood supply). This is because the tail has just one incoming route for blood vessels. The bandage first compresses the veins, preventing blood from leaving the tail and causing fluid to leak out into the soft tissues. The tail then increases in size under the bandage, leading to further compression.

The arterial blood supply eventually stops, starving the tail of oxygen and causing tissue death. Amputation is often the only solution, a routine surgical procedure performed under standing sedation and epidural anaesthesia.

Other than for veterinary reasons, there is no evidence that tail docking has any benefit to horses — including draught horses. In most countries it is illegal to dock a horse’s tail for aesthetic or work-related reasons.

The tail is also a common site for skin disease. Melanomas typically develop on the underside, although the reason for this is unknown. These tumours generally occur when genetic or environmental factors cause instability of the DNA within the melanocyte cell, which then starts to multiply excessively. The under-tail may be susceptible because it has the highest number of melanocytes, or the absence of hair could potentially expose these cells to environmental factors or increased physical stimulus. Sunburn has not been identified as an equine melanoma risk factor.

Tail rubbing is usually due to allergic skin diseases such as sweet itch, insect allergy and recurrent urticaria, and can lead to complete hair loss. Other causes include an infestation of pinworm, an intestinal parasite, which lays its eggs around the anus, or a rare nervous condition called neuropathic pruritis, which amplifies skin sensitivity.

‘Infection nearly killed him’

When vets at B&W Equine examined an emaciated two-year-old cob gelding with supposed fly strike (an infestation with fly maggots) in his tail, it was apparent that elastic bands had been left around his dock.

“Restriction of blood flow had caused systemic infection,” says Lucy Barrow, who was then a veterinary nurse at the practice. “The tissue was necrotic and the infection could have killed him.”

There was no option but complete tail amputation (pictured, below), which was performed by B&W surgeon Chris Wright.

“Once the bone was cut through, a tourniquet was applied to stem bleeding,” explains Lucy. “Many of the blood vessels were so damaged that they were already closed off. It was then important to keep the healing site clean and administer antibiotics to fight any infection.”

The little gelding was christened “Stumpy Sam” and taken on by Lucy, who was anxious to see how he would cope without a tail.

“He didn’t seem too bothered and probably manages better than a thin-skinned thoroughbred,” she says. “He now lives with a herd on Minchinhampton Common.

“Once tissue is dead, the damage cannot be reversed. It’s worth remembering to be careful with tail bandages.”

Ref Horse & Hound; 8 September 2016